The following is an extended English version of the presentation at the Stichting voor de Middeleeuwse Archeologie conference, Dijken, Dammen en Duikers on June 24, 2016. If you would like the Dutch version, contact me. Please acknowledge if citing. – Adam Sundberg

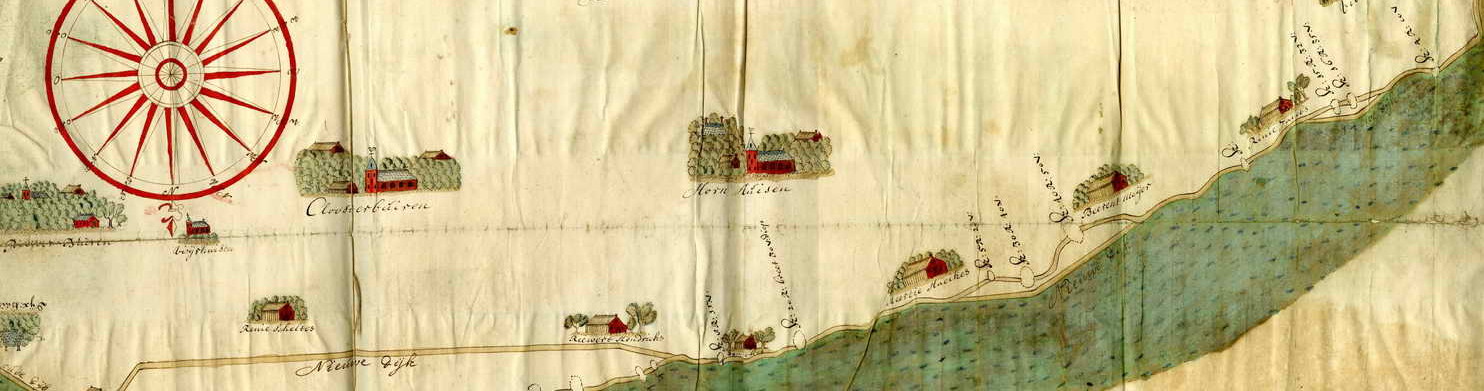

On the 8th of March in 1732, the Dijkgraaf (Dike Reeve) of Drechterland, Wijnant Nieuwstadt wrote a letter addressed to the University of Leiden. It appealed to the eminent natural philosopher and mathematician Willem Jacob ‘s Gravesande to help with “a terrible judgement from God” that had afflicted West Friesland.[1] This “evil,” he stated, was “ruinous for all of the strongest dikes, piles, and krebbingen” in the region.[2] The cause of his alarm was a “worm” that had “eaten through the piles of several West Frisian dikes, as well as those at Den Helder, Texel, and elsewhere.”[3] This “worm” was in actuality a marine mollusk called Teredo navalis that bored into the wooden components of dikeworks across the maritime provinces.

Shipworms were not new to the Netherlands in the 1730s, but they had never appeared so suddenly and with such destructive consequences. This was the first sustained, explosive outbreak of shipworms in the coastal water defenses of the North Sea. The disaster was an early modern media event that prompted dozens of newspaper articles, pamphlets, and books, not to mention hundreds of governmental decrees and resolutions addressing the subject. It generated international attention from enterprising engineers and scientists wanting to profit from the disaster, just as it prompted self-reflection from moralists criticizing the moral fabric of the Netherlands. Shipworms generated widespread interest, anxiety, even fear among contemporaries. The plague of Teredo navalis, in other words, was a mirror that reflected the cultural and environmental history of West Friesland and the Netherlands.

The shipworm epidemic of the 1730s is not unstudied. It has generated sustained (if relatively minor) interest from scientists and historians since the eighteenth century. Despite its broad significance, however, much of the recent historical research on this period covers its economic and technological consequences. This is perhaps unsurprising. The economic consequences of the outbreak were considerable. Between 1732 and 1743, waterschappen across the Netherlands were forced to expend an estimated 8.1 million florins to rebuild dikes and in in West Friesland alone, the total costs for dike improvements have been estimated at 4.8 million florins.[4]  Arriving during an era of secular economic recession in West Friesland and sandwiched in between two deadly epidemics of cattle plague, the economic consequences of shipworm plague were onerous, even disastrous for some communities.

Arriving during an era of secular economic recession in West Friesland and sandwiched in between two deadly epidemics of cattle plague, the economic consequences of shipworm plague were onerous, even disastrous for some communities.

From the perspective of the history of dike technology, shipworms were likewise influential. Dike designs varied, even within a single region like West Friesland, but many employed wooden components, either as wooden palisades or as supporting structures for large, wave breaking cushions. Naturally, shipworm appetites made these designs problematic and water boards across the coastal Netherlands experimented with new dike designs and “remedies” intended to combat this molluscan plague. The extent and speed with which waterschappen implemented these “novel” designs varied, but in West Friesland we can state that the shipworm episode marked a significant breaking point where dike designs increasingly used stone as construction material, either by laying stone in front of the paalwerken and krebbingen (as in parts of West Friesland), or replacing wooden material entirely with gently sloping dikes layered in stone.

In their brief exchange, Nieuwstadt and ‘s Gravesande only implicitly address the pressing economic and technological challenges of the shipworm epidemic, however. Regarding economic concerns, Nieuwstadt merely comments on the impo ssibility of accounting for the costs of dike repair.[5] When asked for recommendations regarding possible technological remedies for the molluscan infestation, ‘s Gravesande’s replied with caution. He critiqued several possible solutions that had been forwarded to him including the application of a special poison to the wood. “I have no knowledge of anything,” he argued, “that can cleave so tightly to wood that after a few years under water and standing up against the beating of waves with remain.”[6] Despite (or perhaps because of) his experience and reputation, he qualified his input. Although he “examined and sought insight into the subject in a limited capacity,” he replied, “I have to admit that I have little to offer toward the stopping of this evil…I have no research, and I’ve found nothing useful from books on the subject.[7] Instead, ‘s Gravesande commented on the similarities between the “North Sea” worm and other shipworms from the Americas, whether the epidemic would disappear on its own, and the animal’s natural and divine origins.

ssibility of accounting for the costs of dike repair.[5] When asked for recommendations regarding possible technological remedies for the molluscan infestation, ‘s Gravesande’s replied with caution. He critiqued several possible solutions that had been forwarded to him including the application of a special poison to the wood. “I have no knowledge of anything,” he argued, “that can cleave so tightly to wood that after a few years under water and standing up against the beating of waves with remain.”[6] Despite (or perhaps because of) his experience and reputation, he qualified his input. Although he “examined and sought insight into the subject in a limited capacity,” he replied, “I have to admit that I have little to offer toward the stopping of this evil…I have no research, and I’ve found nothing useful from books on the subject.[7] Instead, ‘s Gravesande commented on the similarities between the “North Sea” worm and other shipworms from the Americas, whether the epidemic would disappear on its own, and the animal’s natural and divine origins.

These were not unrelated considerations to story of dike adaptation in West Friesland and across the Netherlands. In the absence of prior experience with this type of disaster and ready-made solutions, shipworms became useful tools to discuss a wide variety of issues, some of which may seem only tangentially connected to dike repair. Shipworm commentators discussed natural history, the divine origins of natural disasters, creeping environmental changes like the disappearance of voorland, and the economic impacts of other natural disasters like floods and cattle plague. The considerable attention paid to these subjects compensated for a troubling lack of insight into their predicament and, in general, attempted to answer the following questions:

What were the shipworms? Water authorities, natural historians, moralists, and laypeople each grappled with this most fundamental set of questions. Shipworms were not completely unknown to eighteenth century Dutchmen. European mariners, including the Dutch had had a long relationship with shipworms in foreign waters, particularly as their voyages took them into the tropics. There is even some limited evidence of wood borers in Dutch waters as early as the late sixteenth century. Little of this experience translated to a clear picture of habits, life history, or environmental limits of the mollusk. This was an important question, because it explicitly delineated the scope of Dutch vulnerability and the likely duration of the plague.

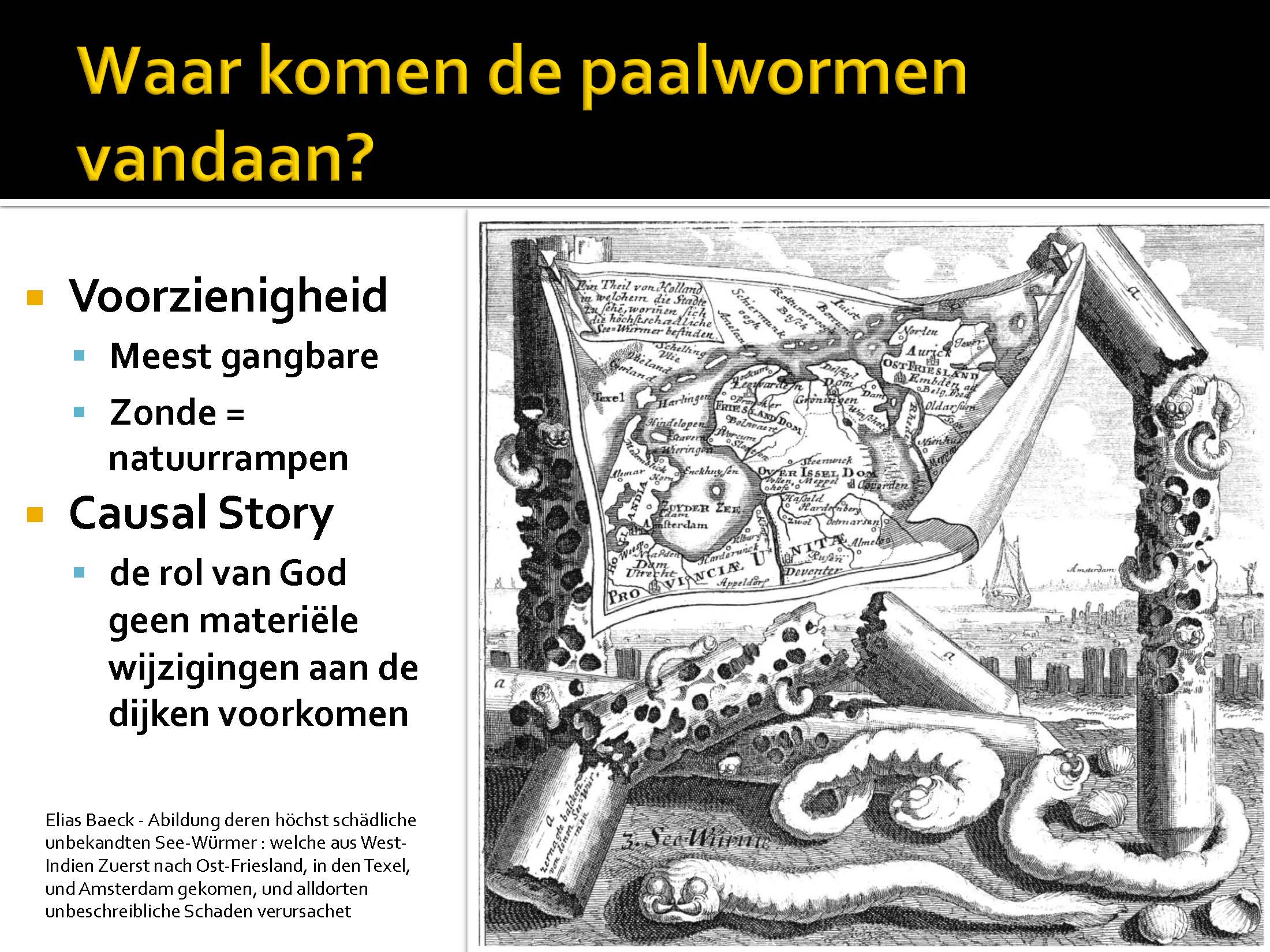

Prior experience likewise offered only limited insight to a second major question: where did the shipworms come from? Were shipworms indigenous to Dutch waters? Did they simply explode in population because of some environmental influence? Or was it because of Dutch sin and God’s providential wrath? What if shipworms were foreign invaders? Were they unwelcome passengers on East or West Indiamen? This set of questions addressed more than the origins of the disaster, but its ultimate character. They determined whether the epidemic was natural or supernatural; whether this would be the first of several outbreaks; and whether adaptive measures had any chance of success.

Both sets of questions were important because they explicitly framed the disaster as knowable and, therefore, potentially reversible. They laid the groundwork for what political scientist Deborah Stone terms, “causal stories,” or “images” of perception and interpretation that frame disaster response.[8] Simply put, one cannot make changes after a disaster unless one understands what happened. In the context of West Frisian dikes, “causal stories” affected dike adaptation.

These “causal stories” fundamentally grounded a third set of questions: how could the shipworm be stopped? Should solutions focus on killing the mollusks? Should they focus on preventing infestation of the wood? Should the solution be chemical? Mechanical? Spiritual/moral? Should the solution draw upon historic dike designs or depend on innovations? Knowledge of what they shipworms were and where they came from (in other words, the foundations of causal stories), determined which solutions were acceptable.

For the remainder of this talk, I want to outline how these questions were addressed in West Friesland. In doing so, we can develop a clearer picture of why water authorities chose the designs that they did.

What were the shipworms

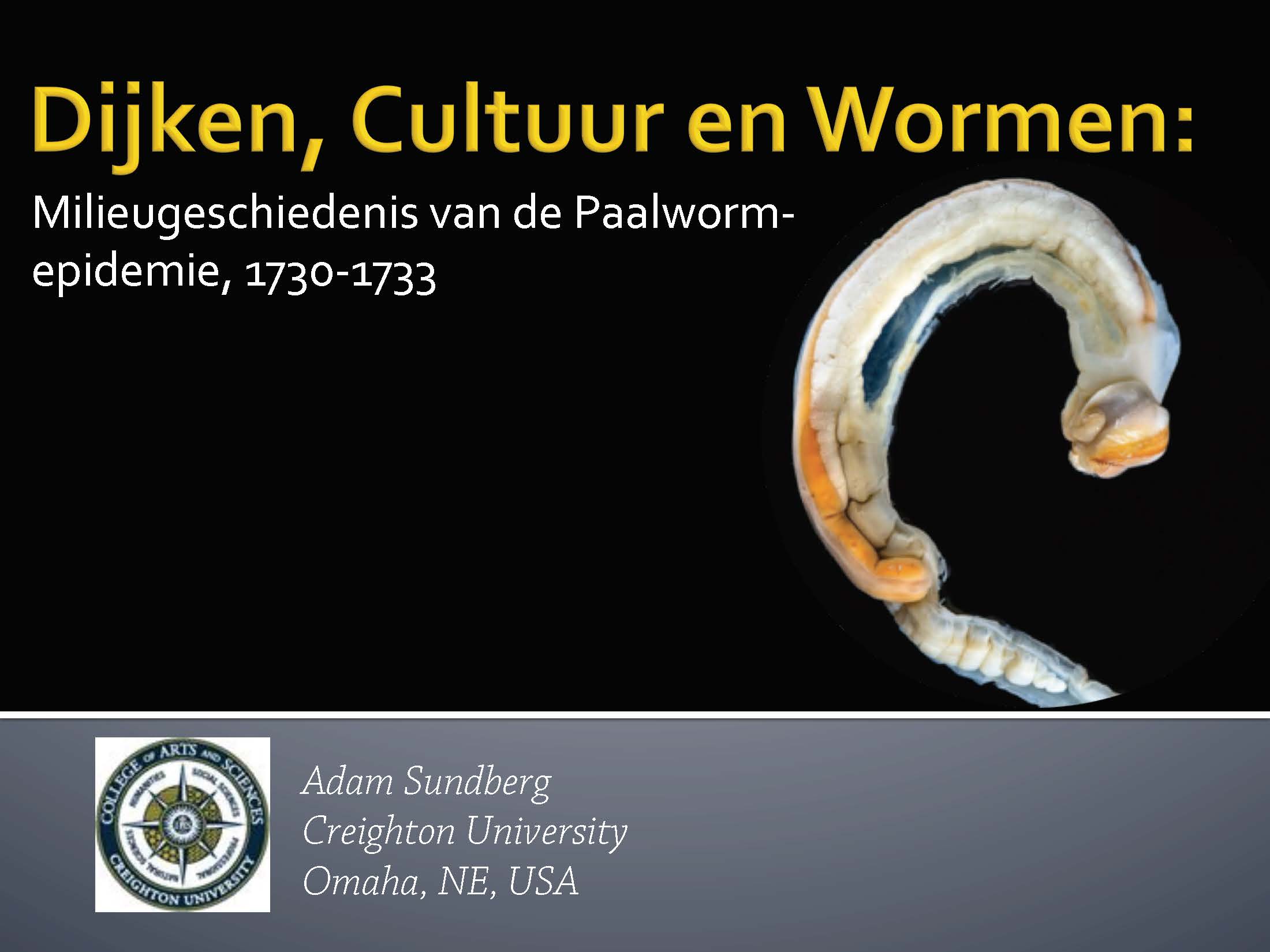

What were they shipworms? Today, we understand the naval shipworm to be a marine mollusk of the family Terenidae. Shipworms are highly specialized bivalves that consume and live in wood submerged in (to a large extent) coastal areas. They are worm-shaped and have two shells that are used as boring tools. T. navalis is very widely distributed today, from the Sea of Japan to the Swedish coast of the Baltic Sea.[9] This is partly because T. navalis had relatively wide tolerance for environmental conditions. Despite this, temperature and salinity are its two most significant limiting factors.

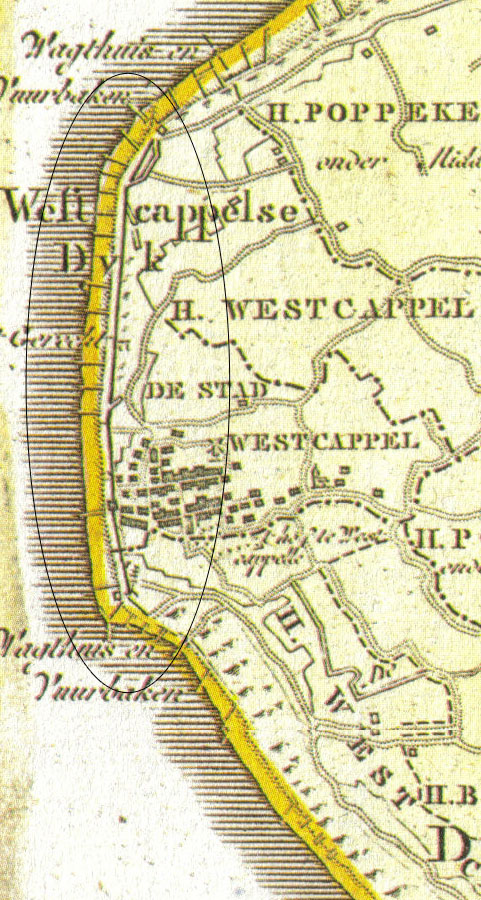

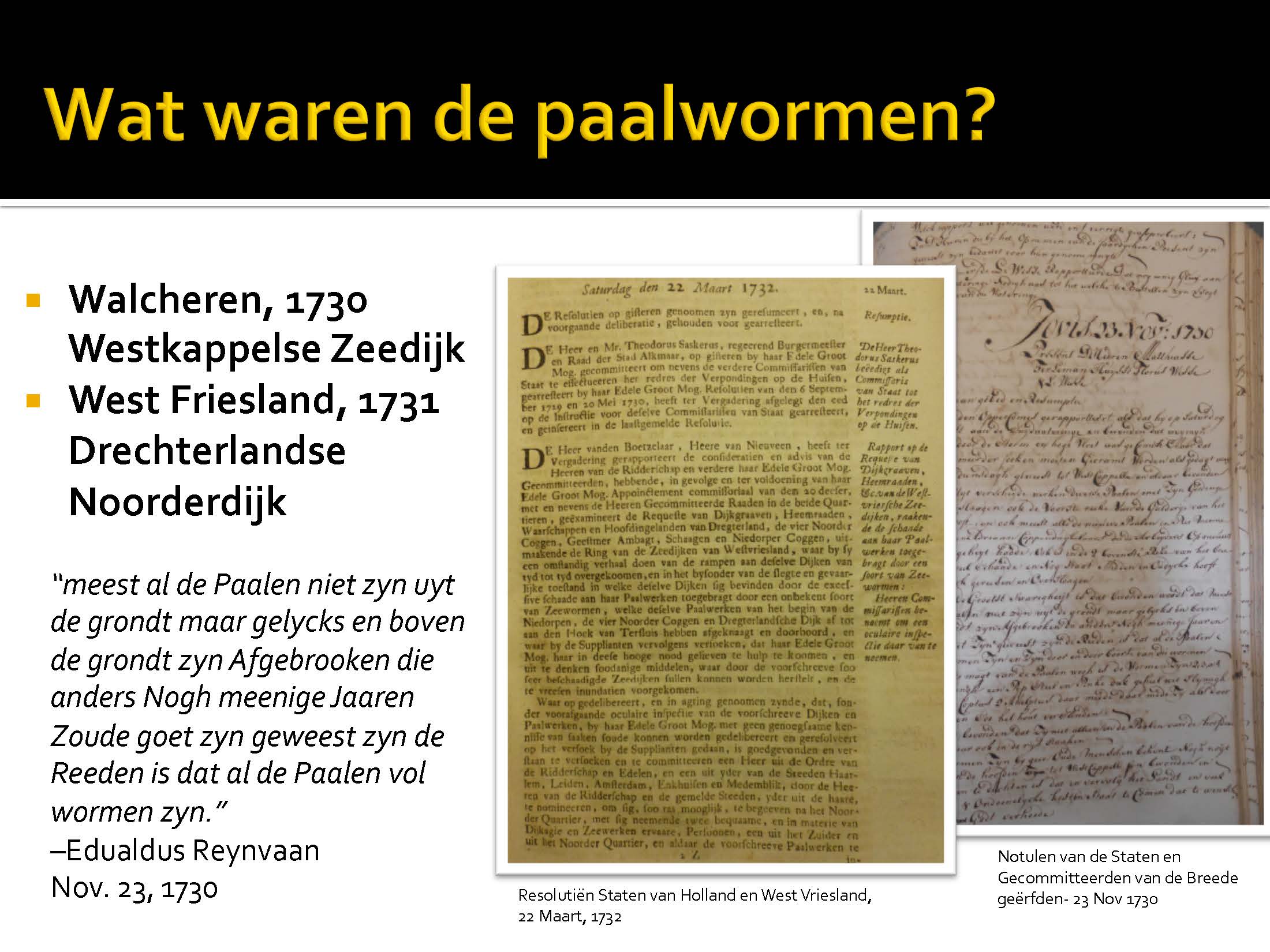

None of this was known in 1730, however, when the shipworm epidemic began in the Netherlands. First appearing on the island Walcheren in Zeeland during a November storm, the local upper commissioner for the Walcheren water board, Edualdus Reynvaan noted his surprise at this minor storm’s damage: “most of the piles, that otherwise would have been good for years, were not driven out of the ground, but instead were broken above the ground and the reason is that the piles are full of worms.”[10]

Reynvaan was the first to describe the shipworm in detail. He noted that the worms were “2,3,and 4 thumbs in length and a pipe stems thickness entirely of slime foulness.” He went on to note that they were found, not only in the hoofden, but also in the rijsstaken. By the end of the year, Reynvaan discovered that they did not discriminate between oak, birch, willow, or alder and that they infected green and older wood. All of these initial findings would be broadly disseminated across the Netherlands, including to West Friesland, where Nieuwstadt would then forward them to ‘s Gravesande.

The West Frisian theater of the shipworm plague would begin under similar conditions in September of 1731. A wier and palen inspection discovered that strong northern winds and high water had knocked loose several piles along the Drechterlandse Noorderdijk. This was not unusual, however. It was only after rumors of “extraordinary sea worms” in the piles of Texel and Den Helder that the shipworm became a West Frisian disaster.[11] Initial observations of the threat mirrored those in Zeeland. Observers described the worms’ length, their preference for pine wood, and their infestation up to the high tide mark.[12]

It is important to note that these initial observations served as a foundation for later attempts to determine the biology and environmental limits of the shipworm. Many of these early reports were collected in the periodical Europische Mercurius, which published a special “Bericht de plaage der Wormen in the Paalwerk der Dykagien van Holland en Zeeland.” This report drew on the very same dike reports coming out of Zeeland and West Friesland. Knowing what the shipworms were (and were not) was an important precondition to dike repair. This information was doubly important because “strange and outrageous rumors and false descriptions being spread in foreign countries.”[13] One German newspaper reported that Amsterdam’s houses had begun to collapse when their foundations were eaten by worms. Another Swiss newspaper reported that the worms’ heads’ were as hard as iron, they could be two feet long, and the dug holes directly into the dike. Reports like the Europische Mercurius were important because they drew on firsthand observations by dike officials.

Even so, the waterschappen were the first to admit that they needed more information. Even before the publication of the special Mercurius report in August, the “Heeren Dykgraven en Regenten van Drechterland” published a request in the Amsterdamse Courant for anyone who had information or had developed measures against the shipworms to send them to Hoorn and Enkhuizen.[14] In response, Hoorn and Enkhuizen, as well as The Hague, received a flood of suggestions. The earliest reports about what the shipworms were useful because they vetted the most outrageous proposals. Many proposals were rejected because they were unfeasible or too expensive, but many were also rejected because the proposal showed no understanding of the worm itself. Pieter Scheiber of Hamburg’s proposal, for instance, was rejected despite his detailed list of expenditures, because he “Toont groote kennis van geld te hebben, maar geen kennis van de aard der wormen.”[15]

These early questions about what the shipworms were explicitly framed that problem as an engineering problem, albeit one with no clear solutions. Empirical observations confirmed the species was marine (and could not live in fresh water), that it preferred green wood, but would embed itself in almost any native European wood up to the high tide mark, as well as the seasonality of the outbreak. These were important observations because they determined the scale of vulnerability of West Frisian dikes. Following the 1731 inspection of the Vier Noorder Koggen dikes, the only areas that were not infected were those that dried on a daily basis.[16] These reports also gave observers no reason to believe the shipworm infestation would end on its own. In his reply to Nieuwstadt, ‘s Gravesande noted with “groot leet,” “dat ik geloven weeten dat men sigh sonder rede vleyt dat dese plaag zal komen te cesseeren…het is wel apparent dat de schade onvergelykelyk grooter zal syn als tot noch toe is begroot.”[17] A remedy needed to be found, but what kind would be effective?

Where did the shipworms come from?

The initial response to shipworms was the search for a mechanical remedy, but by 1732 the realm of available solutions had widened considerably. This was largely due to the widespread popular response to the call for solutions. Remedies, however, came in many different forms. Poisons, smeersels, iron buttresses, and new designs for dikes arrived from across Europe. As news of the disaster spread, spiritual solutions became more popular. Finally, the shipworm epidemic sparked a minor outpouring of scientific literature on the subject. Between 1732 and 1735, the shipworm epidemic became a truly public, national disaster. In addition to describing the shipworms, these popular discourses addressed a second critical question: where did the shipworms come from? The question of the shipworms’ origins was a necessary component of a causal story.

From the perspective of modern scientists, shipworms are still somewhat a mystery. They are considered a “cryptogenic species”; they have no known origin.[18] The earliest accounts of shipworms in European waters date to the 4th century B.C., though it is impossible to determine whether this was T. navalis.[19] Dutch mariners certainly came into contact with shipworms on a consistent basis after the expansion of Dutch trade into the tropics in the late 16th and 17th centuries. Dutch shipbuilders already considered T. navalis the principle hazard of tropical commerce by the early 17th century. Almost every VOC ship bound for Asia had shipworm “verdubbelen” – a triple layer of oaken hull, a layer of lead or hair nailed to the oak, and a soft pine wood over that.[20]

Shipworms may have even arrived in the Netherlands prior to 1730. Reports noted damage possibly resulting from shipworms in Dutch waters as early as the 1580s. However, this damage was either limited to marine vessels or the damage cannot be conclusively linked to T. navalis.[21] Contemporaries to the shipworm epidemic could likewise find no agreement as to the origins or duration of the shipworms presence. Adriaan Bommenee, hoofd van openbare werken in Verre, noted in retrospect that the shipworm had been known to everyone “in memoriale tyden,” but they had always existed in limited numbers.[22] On Walcheren, Edualdus Reynvaan argued that “Ik en hebbe in myn tyd van 30 Jaren, dat aan de Dyk hebbe verkeert noit een worm ondekt; oude arbeiders van 80 Jaren verklaren ook noit ondervonden te hebben. Ik en vinde ook in geen Notulen van het Jaar 1550 af dat er mentie van sulken quaad wort gemelt…”[23]

The shipworm epidemic also catalyzed intense scientific interest. Between 1733-35, a number of Dutch and international scholars contributed their insights into the origin and biology of the shipworms. Many recognized that this was a prime opportunity to produce meaningful, very public work. Jean Rousset de Missy, for instance, noted that “The Damage, which hath been caus’d by certain Sea – Worms, to the Pile-Works of the Dykes of Zealand, North -Holland Friesland, and the Coast of Flanders, hath made so much Noise, that it is no Wonder the Curiosity of the Publick, and particularly of Gentlemen who employ themselves in the Study of Natural Philosophy, hath been awaken’d to look narrowly into this Phenomenon.”[24] Perhaps the most famous contribution came from the Prussian natural historian Gottfried Sellius, whose observations would later serve as the basis for Linnaeus’ taxonomy of the species. Although much information was shared (or copied) between the authors, their conclusions could be widely varied. In his 1735 treatise on the shipworm, Abraham de Bruyn, listed eight different theories as to the origin of the shipworm, from “they came from the east or west indies,” “they came from heat and siltiness of the North Sea,” to “they developed out of oyster banks.”[25] Authors differed in their conclusions about the role of sea temperature, salinity, and the means of reproduction. What De Bruyn, Belkmeer, Bommenee, and Reynvaan could agree on (and this was broadly felt in West-Friesland after 1731 as well), was that the ultimate origin of the shipworm plague was God.

By far the most common explanation for the arrival of the shipworms was God. Shipworms were a judgment from God for the sinful state of the Netherlands. It is easy to dismiss this discourse as formulaic. Divine judgment, after all, was not an explanation for disasters specific to the eighteenth century. Several conditions about the shipworm epidemic appealed more strongly than to the role of God other disasters. First, it’s timing could not have been less ideal. By the early eighteenth century, much of the coastal Netherlands was undergoing a secular economic recession. West Friesland was particularly hard hit. A number of provinicial governments, as well as the Staten Generaal declared “Dank, Vast, and Bededagen” to ask God to end this era of disaster. The Staten van Holland en Westvriesland, for instance, called on all of the United Provinces to observe a day of repentance on the 11 of May, 1733 because of the “vermindering van Navigatie en Commercie, door swaare Waatervloeden, door ongemeene siektends en starfte onder Menschen en Rundvee, en nu laatstelijk door een ongewoone plaage van schaadelijk Gewormte in Paalen en Houtwerken.”[26] Only a decade earlier, the first of three epidemics of cattle plague (likely rinderpest) had swept across the Netherlands, decimating herds and memories of previous disasters, including the flood 1675 had not yet faded. In this climate of dearth and disaster, the shipworms arrival signaled a renewal of hard times and further confirmation of God’s role.

Staten van Holland en Westvriesland, for instance, called on all of the United Provinces to observe a day of repentance on the 11 of May, 1733 because of the “vermindering van Navigatie en Commercie, door swaare Waatervloeden, door ongemeene siektends en starfte onder Menschen en Rundvee, en nu laatstelijk door een ongewoone plaage van schaadelijk Gewormte in Paalen en Houtwerken.”[26] Only a decade earlier, the first of three epidemics of cattle plague (likely rinderpest) had swept across the Netherlands, decimating herds and memories of previous disasters, including the flood 1675 had not yet faded. In this climate of dearth and disaster, the shipworms arrival signaled a renewal of hard times and further confirmation of God’s role.

It is likewise easy to dismiss this discourse as the superstitious paranoia of early modern societies. The shipworm was strange, however. Common on voyages to the tropics, shipworms were largely unknown in the Netherlands. The scale and severity of the 1730 outbreak was absolutely unheard of. With no prior experience and no proven explanation of natural origin, divine explanations were a logical conclusion.

As part of a “causal story,” divine judgment could work with naturalistic explanations or against them. For instance, although Reynvaan, Bommenee, and De Bruyn all subscribed to naturalistic explanations for the sudden appearance of the shipworms (mostly due to climate changes), all attributed the shipworms ultimately to God. As a causal element of the shipworm epidemic, God’s role did not preclude material changes to dikes. Naturally, an exclusive form of providentialism would not fit the causal stories of dike officials like Reynvaan or Bommenee or wetenschappers advertising remedies for the shipworm epidemic like De Bruyn.

Many commentators during the eighteenth century had less interest in dike repair, however. Dutch morality in their view also required saving. A wave of providentialist books and pamphlets appeared between 1732 and 1735 warning of “Gods slaande hand over Nederland.” The shipworms, according to many pamphlets, were more than a sign of God’s displeasure; they were a sign of more terrible disasters in the future. Friesland’s 1732 plakkat for a Dank, Vast, en Bededag echoed much of the early confusion and frustrations of the waterschappen. The shipworms, it stated, are “Voorwaar een vreeslyk Oordeel Gods alhier nooyt bespeurt, waar af de oorspronk nog de voorteelinge, de kragt nog de sterkte tot nog toe door geen Menschelyk vernuft of schranderheyd kan gepeylt of nagespeurt werden, veel min eenige Remedie uytgevonden om de Goddelyke Plage af te wenden.”[27] In this causal story, the fact that shipworms evade explanation and remedy is justification of their divine origins and a divine solution.

Between 1732 and 1735, Dutch commentary on shipworms dramatically expanded. Water management officials remained actively involved, but new participants like natuurwetenschappers, moralists, and the broader public offered different interpretations of what the shipworms were and where they came from. These interpretations formed the basis for “causal stories” that turned a confusing, dangerous situation, into a problem that could be solved.

How could the shipworms be stopped?

Water boards’ primary challenge in the initial period of the outbreak had been its novelty. By 1733, new information and an expanded public discourse created a number of different options for dike authorities tasked with rebuilding West Frisian dikes. Moralists who held exclusive providentialist views, presented spiritual solutions like public prayers, penitence, and remembrance. Wetenschappers offered solutions that drew on their empirical observations of the biology and ecology of the mollusk. The wealth of proposals sent to West Friesland and The Hague at the request of the waterschappen tended to favor innovative and (supposedly) exclusive remedies. The waterschappen were publically open to new designs and conducted extensive tests of many. Causal stories framed each of these realms of action. In the end, they favored a capital-intensive solution based on established dike designs. This solution adhered to a causal story grounded in new knowledge of shipworms, but one that ultimately turned shipworms into flood risks.

The response from waterschappen began immediately, but reports were often couched in tentative language. A letter from Edualdus Reynvaan, for instance, noted that “little can be said with certainty” about how to remove the mollusks.[28] In general, waterschapsbestuur remedies can be roughly divided into two realms: 1. Rebuilding dikes with little alteration 2. Relying on maritime experience with the shipworms. The initial response was simply to repair with some minor alterations. Later, inspectors from a commission established by the Staten van Holland presented a “nieuw manier van dijkagie” whereby the krebbingen that had held the wier in place would be removed. Instead, piles would be perpendicularly driven through the wier to fasten it to the sea floor.[29] This method proved both expensive and susceptible to damage by waves.[30]

At the same time, the Holland commission was testing a variety of proposals from near and far. Many remedies drew, to a large extent, on the measures taken to protect ships. Reynvaan noted their experiments with the piles. They burned the outside of the piles, coated them with tar, harpuis, and hair, and noted their effectiveness. They also noted their unworkable costs. Maritime experience with shipworms was useful, it seems, but it was not workable on the scale of Dutch coastal defenses. In response, they turned to outside information. Indeed, the vast majority of solutions available to the waterschappen of West Friesland came from outside their institutional organizations. Suggestions came from as far afield as Switzerland, France, and Italy. Many of these remedies were tested in West Friesland and the majority were variations on the maritime solutions tested in 1732. One of the more interesting solutions drew on a different maritime strategy to protect ships, this time by cladding the outside of dikes in large, flat copper wormspijkers. Records from England date this technique with lead to as early as the 17th century, and possibly as early as the ancient Phoenicians.[31] Versions of this remedy were tested in Zeeland and West Friesland. In Drechterland in 1733, test piles with copper cladding were found to be the only piles that were not infected, but because of their great expense, “no award for this test can be given.”[32] While this method was too expensive to be employed on every dike, they were used to protect areas with little to no land in front of dikes, such as harbors or sluices.[33] In sum, the initial response on the part of waterschappen was to focus on the mollusks themselves. From the perspective of causation, animals were the source of their problems. Their solutions focused on those animals and drew on centuries of received wisdom from mariners. Dikes were not ships, however. Years of testing based on maritime knowledge of the worms reinforced the effectiveness of their methods, but proved impossible to employ on such as large scale. A different solution was needed.

A second set of solutions came from wetenschappers. They saw the vacuum of information available to waterschappen as an opportunity. Cornelis Belkmeer addressed his treatise to the commission established by the Staten van Holland to inspect the West Frisian dikes. Indeed, the majority of the natural historical treatises produced about shipworms between 1733-1735 self-consciously advertised the practical benefits of th e “new” knowledge they produced. Unlike other participants, these authors tended to promote solutions that drew on their new findings. For instance, a source of debate amongst authors was the reproduction of shipworms. Many authors observed a white slime on the outside of the piles and concluded it contained shipworm eggs. As a result, Belkmeer suggested burning the outsides of the piles to harden them and then scraping the slime with “yzere schrapers en styve borstels.”[34] Although none of their solutions were accepted, a few were considered. The commission for the repair of the West Frisian sea dikes estimated the cost of Rousset’s remedy at 1.36 million guilders, but left no record of its success or failure.[35] Like the early proposals and experiments conducted by the waterschappen, the wetenschappers largely interpreted the cause of the disaster to the shipworms themselves. Unlike the waterschappen, however, they typically sought a deeper level of causation. They sought new information about the biology and origins of the shipworm that might offer insight to potential remedies.

e “new” knowledge they produced. Unlike other participants, these authors tended to promote solutions that drew on their new findings. For instance, a source of debate amongst authors was the reproduction of shipworms. Many authors observed a white slime on the outside of the piles and concluded it contained shipworm eggs. As a result, Belkmeer suggested burning the outsides of the piles to harden them and then scraping the slime with “yzere schrapers en styve borstels.”[34] Although none of their solutions were accepted, a few were considered. The commission for the repair of the West Frisian sea dikes estimated the cost of Rousset’s remedy at 1.36 million guilders, but left no record of its success or failure.[35] Like the early proposals and experiments conducted by the waterschappen, the wetenschappers largely interpreted the cause of the disaster to the shipworms themselves. Unlike the waterschappen, however, they typically sought a deeper level of causation. They sought new information about the biology and origins of the shipworm that might offer insight to potential remedies.

A third set of potential solutions was spiritual. Dank, vast, and bededagen were the core remedies, though many providential texts also recommended more comprehensive individual spiritual renewal as well. According to the “sin economy” of divine providence, Dutch sin directly translated to natural disasters. This causal framework made little distinction between “kinds” of natural disasters. Veepest, overstromingen, fires, and shipworms all required the same solution. In fact, the strangeness and unprecedented nature of the shipworm th reat was ideally suited to providentialist interpretation. Providential remedies were likewise flexible. While a few exceptional moralists fatalistically warned that attempting to remove the shipworms would only bring more terrible punishments, most easily mingled with secular solutions.[36] Indeed, the success or inventiveness of remedies against the shipworms was also often attributed to God. Henricus Engelhardt, for instance, attributed his “goede sufficante middellen” to his “groote zorgvuldigheid en smekinge tot God.”[37] Providential remedies were not insignificant. Unlike many of secular plans or remedies, spiritual solutions were invested with institutional authority from both church and state. The concurrent performance of spiritual and secular remedies speaks to confidence in both.

reat was ideally suited to providentialist interpretation. Providential remedies were likewise flexible. While a few exceptional moralists fatalistically warned that attempting to remove the shipworms would only bring more terrible punishments, most easily mingled with secular solutions.[36] Indeed, the success or inventiveness of remedies against the shipworms was also often attributed to God. Henricus Engelhardt, for instance, attributed his “goede sufficante middellen” to his “groote zorgvuldigheid en smekinge tot God.”[37] Providential remedies were not insignificant. Unlike many of secular plans or remedies, spiritual solutions were invested with institutional authority from both church and state. The concurrent performance of spiritual and secular remedies speaks to confidence in both.

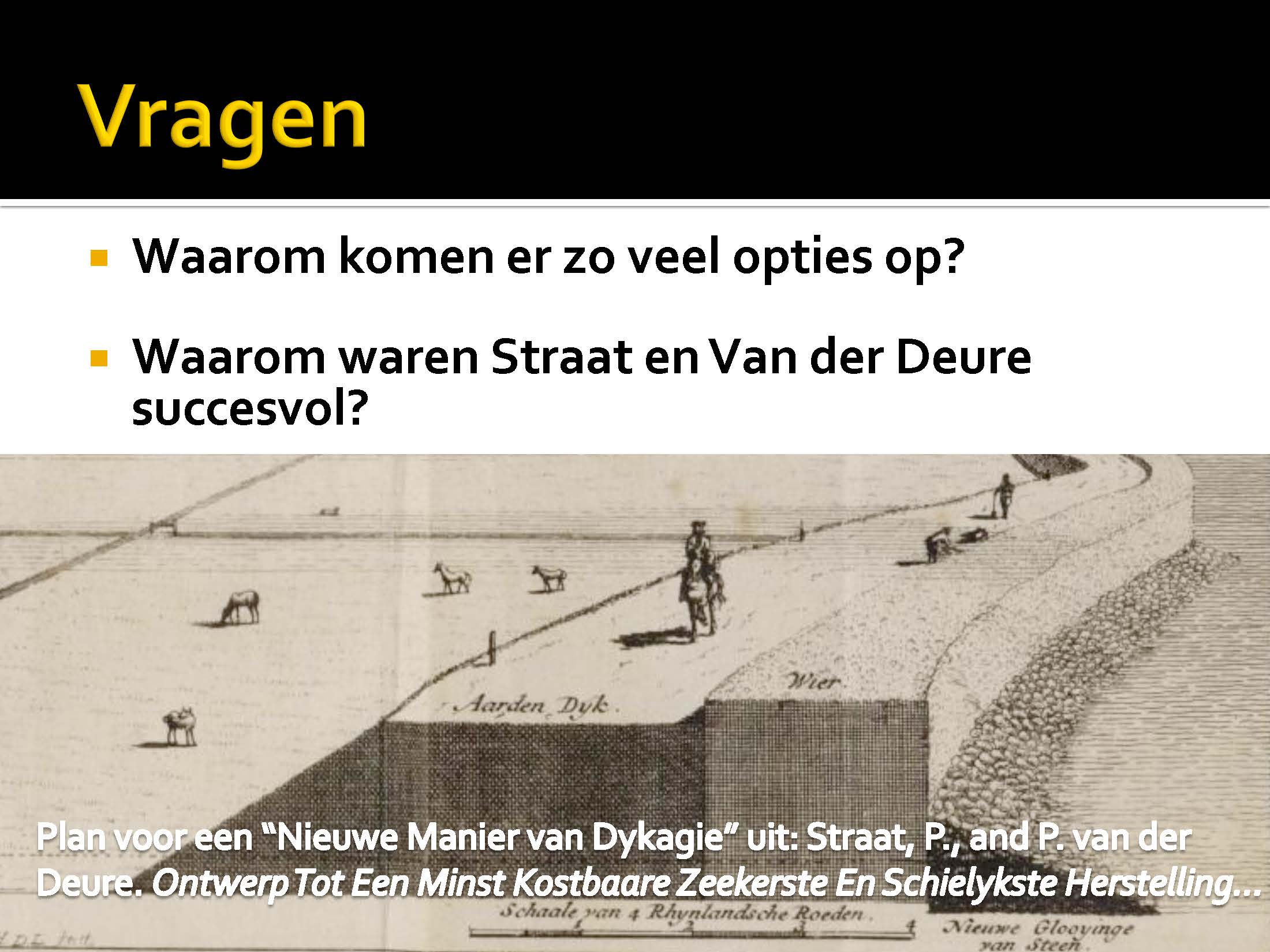

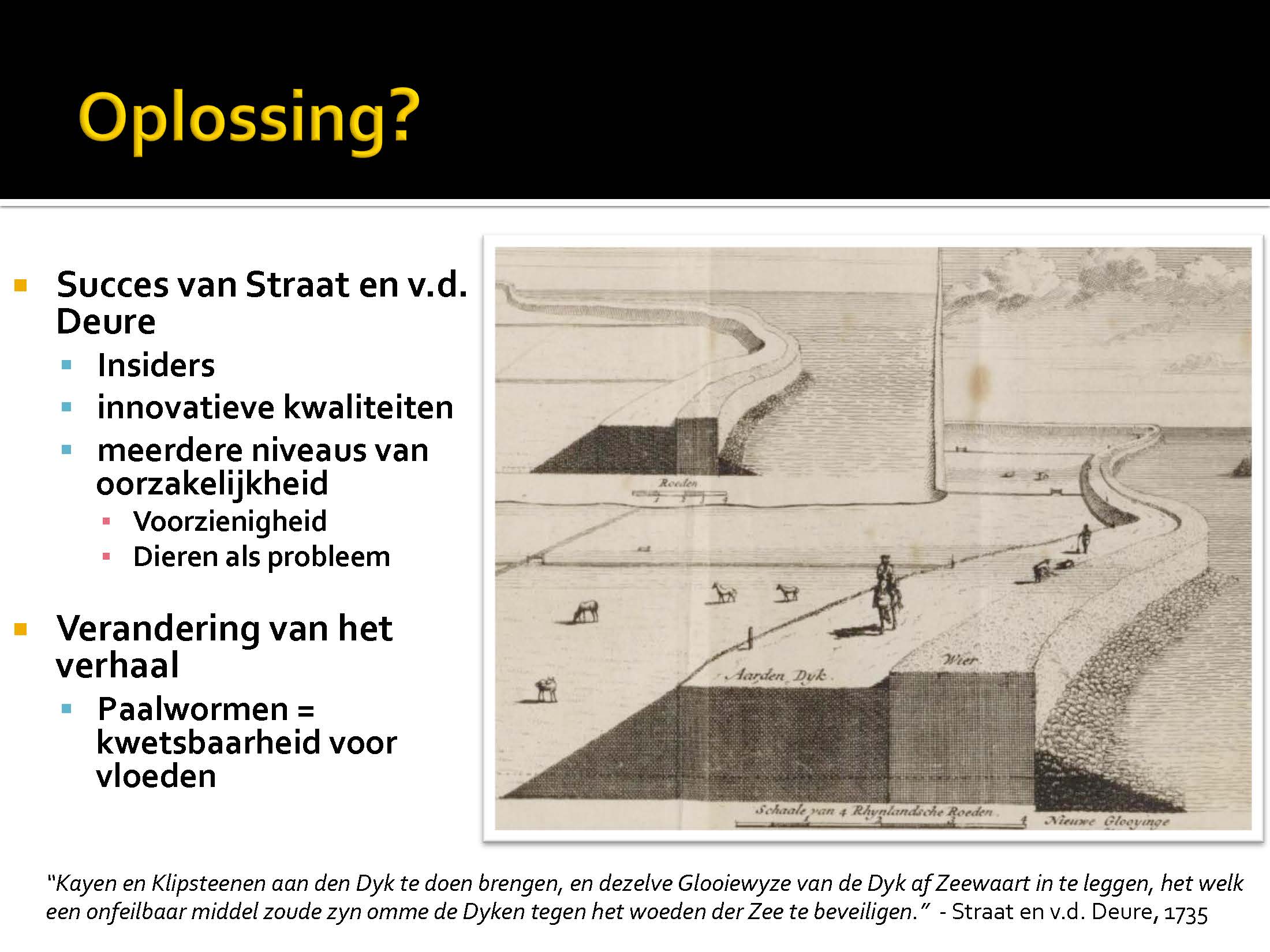

A final set of potential solutions developed out of the exhaustion of other options. Although some had proved feasible, none fit the requirements of being impervious to shipworms, durable against the sea, and cost effective. The solution in West Friesland developed out of a reassessment of the nature of the disaster. Why was Pieter Straat and Pieter van der Deure’s design so successful? Naturally, it helped that both were waterbestuurders in West Friesland. They promoted the innovative qualities of their designs. They called their proposal a “nieuwe manier van Dykagie” never before used, which “Kayen en Klipsteenen aan den Dyk te doen brengen, en dezelve Glooiewyze van de Dyk af Zeewaart in te leggen, het welk een onfeilbaar middel zoude zyn omme de Dyken tegen het woeden der Zee te beveiligen.”[38] This is perhaps an overstatement. The use of stone on the seaward slopes of dikes date back to at least the 16th century from the journals of Adries Verlingh. Straat and van der Deure’s designs could likewise be considered modifications to existing dikes rather than a completely new design. Rather than removing the wier and palen completely, stone was gradually used to cover the outermost slopes of the most threatened dikes.

More than than that, Straat and Van der Deure proposed a solution that drew on multiple levels of causation. It drew on providential (even existential) language, crediting God for their inventiveness and calling on God to protect the Netherlands. To a certain extent, they acknowledged the causal significance of the shipworm animals. Their design worked because shipworms could not infest wooden components hidden under layers of stone.

Perhaps more important was the degree to which their design removed shipworms from the equation. Shipworms are almost an afterthought in their proposal. The same animals whose mysterious origins, spread, and existence had proved so problematic for waterbestuurders and terrifying for the broader public were largely ignored. Straat and van der Deure were successful because they shifted the causal story to familiar territory: flood vulnerability. Their designs would be beneficial regardless of the shipworms. Even if the “zeeworm geheel en al ophield, en nooit weder te voorschyn kwam,” they argued, the dikes would be left stronger and cheaper to maintain in the long term.[39] The “grootste bekommering ontstaat in stormen en tempeesten, dat men niet kan ontdekken noch verzekert zyn.”[40] They also advertised the proposal as a measure to prevent the loss of coastline, an ever present issue that had necessitated the creation of wierdijken in the first place. Shipworms had already catalyzed widespread public participation in water management, dike design, and the natural history of the mollusk. They inspired numerous designs, patents, and books promoting remedies and new ideas about the cause and solution to the epidemic. In the end, it was only when shipworms had been converted back to the familiar threat of inundation that a suitable remedy was accepted.