As I left the biennial conference of the European Society for Environmental History, I passed a senior scholar explaining why he was headed back to his hotel early. “This heat is unbearable,” he stated, “it’s too hot to think.” Temperatures in Versailles, France (the location of the 2015 meeting) hovered between 95-100 degrees for four straight days and by one account, became the highest July temperatures in the Paris region in 40 years. Public transportation to and from Versailles coped with frequent heat-related delays as train cars turned to saunas, pedestrians walking through the city scampered from one area of shade to the next, and long daylight hours delayed sleep until indoor temperatures reached a comfortable level (usually sometime around 1am). The conference venue offered little respite from the heat. The rooms at the Université de Versailles St-Quentin-en-Yvelines (our host) allowed little air circulation and the high turnout of the conference (wonderful in every other way) only exacerbated the discomfort. Panel chairpersons propped open doors to tempt the occasional cross breeze and after the first day, people began carrying multiple water bottles.

It is tempting to reduce the experience of ESEH 2015 to this discomfort, but despite the best efforts of the French summer, few people I’m sure would deny the value of the conference. For historians of European environmental history, ESEH is a premier event. Scholars come together from around the world to discuss cutting-edge research, show off “experimental” forms of presentation, and network with like-minded scholars. While not a huge event (I heard approximately 400 attended), ESEH showcases the surprising maturity of a regional discipline still young enough that the founding generation of its scholars still actively participate. Its manageable size is one of its greatest attributes, as graduate students find themselves on panels with established scholars or sharing lunch with luminaries in their field. ESEH has typically been (and this year was no different) an accessible, friendly, and unfailingly interesting experience.

It is impossible to summarize a conference like ESEH. Papers addressed topics from over a millennium of history, on subjects from Finland to Canada, using methodologies ranging from quantitative modeling to analyses of visual imagery. It is a long-term goal of mine to compare this conference against past iterations to tease out thematic trends, just as I’ve already begun doing this for the annual conferences of the American Society for Environmental History (ASEH). In the meantime, my personal impressions will have to suffice.

The conference’s 90 panels offered a wide variety of choice, and (like the best conferences), attendees were presented with an embarrassment of riches that forced them to choose between concurrent panels that suited their interests. I typically gravitate to panels at conferences that feature disaster scholarship, the history of water and climate, innovative digital tools, and scholarship on the Low Countries. Despite such broad criteria, I rarely feel overwhelmed by my options at other conferences, but ESEH 2015 seemed to specialize in these topics. The first session on the first day, for instance, featured panels and papers on weather and food, GIS approaches to soil carbon sequestration in colonial Mexico, pre-modern flooding, disaster perception, and a roundtable on “Writing an Environmental History of Europe.” Of course some panels and papers were more impressive than others, and one can’t always choose the best, but I want to focus in this post on some of the more innovative or interesting of my experiences at the conference.

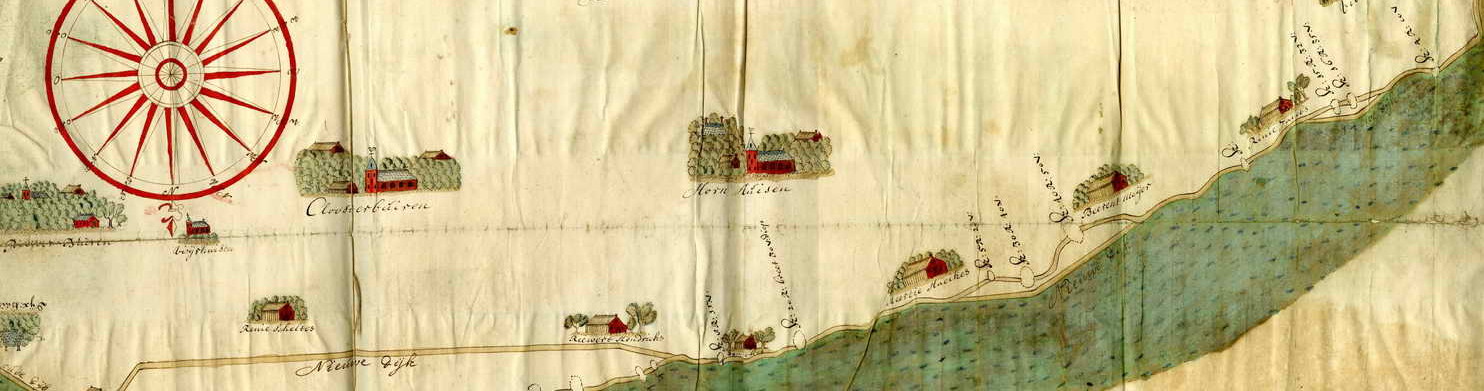

My own paper was featured in one of the earliest sessions in the conference and featured many of the “challenges and limits” of the venue. Entitled “Premodern Environmental Challenges and Limits,” and chaired by Richard Unger of the University of British Columbia, the panel consisted of myself, Kathleen Pribyl of the University of East Anglia, and Kieran Hickey of University College Cork. Like many panels to follow, the room quickly reached capacity. Despite initial technical difficulties, Pribyl initiated an engaging evaluation of the interrelationship between ecological challenges in the late Medieval period as a challenge for urban development. Hickey followed with an overview of a series of port registers that he hopes to mine for their insights into animal populations and their uses in early modern Ireland. My own paper addressed the second outbreak of cattle plague in the Dutch Republic and the influence of a confluence of disasters in the 1740s that mediated response. Like many panels constructed by the program committee, the panel appeared to show considerable breadth in geographic and temporal scope. Despite this, Unger sought unities between the subjects and the liveliness of the Q&A demonstrated a good degree of audience curiosity. Having worked primarily on shipworm-related research during my time in Holland, my presentation was also a welcome return to another familiar subject.

My own paper was featured in one of the earliest sessions in the conference and featured many of the “challenges and limits” of the venue. Entitled “Premodern Environmental Challenges and Limits,” and chaired by Richard Unger of the University of British Columbia, the panel consisted of myself, Kathleen Pribyl of the University of East Anglia, and Kieran Hickey of University College Cork. Like many panels to follow, the room quickly reached capacity. Despite initial technical difficulties, Pribyl initiated an engaging evaluation of the interrelationship between ecological challenges in the late Medieval period as a challenge for urban development. Hickey followed with an overview of a series of port registers that he hopes to mine for their insights into animal populations and their uses in early modern Ireland. My own paper addressed the second outbreak of cattle plague in the Dutch Republic and the influence of a confluence of disasters in the 1740s that mediated response. Like many panels constructed by the program committee, the panel appeared to show considerable breadth in geographic and temporal scope. Despite this, Unger sought unities between the subjects and the liveliness of the Q&A demonstrated a good degree of audience curiosity. Having worked primarily on shipworm-related research during my time in Holland, my presentation was also a welcome return to another familiar subject.

Day two featured one of the “experimental sessions” chaired by Verena WIniwarter and led by four graduate students of Alpen-Adria University, Klagenfurt in Austria. Rather than individual papers, this interdisciplinary cohort of PhD candidates led the audience along a “guided tour” of the water history of Vienna based on historical documentation, photographs, digital GIS-based reconstructions, and visible traces left in the cityscape. The students mixed humor, visualizations, and a keen sense of the history of their subject and in the end, offered a social ecology of the transition from Vienna as a site of agricultural to industrial production. They drew explicitly on the Viennese attention to “socio-natural sites” and the manner in which social practices and material arrangements reshaped nature. Although I’ve never been to Vienna, their presentation’s rich visuality engendered a vague sense of familiarity. Indeed, I began asking myself how much of this history was specific to Vienna and whether one could transpose their model of research and presentation to other contexts. This, I thought, would be a fantastic research project for undergraduates (albeit in a more condensed and manageable format). Rather than a powerpoint presentation showing a journey through Vienna, I imagined a story map highlighting key moments of environmental change back home. It would be a valuable exercise that could simultaneously teach students about web-based digital mapping, historical research, and spatio-narrative storytelling. I wasn’t alone. The first question from the audience asked whether they intended to distribute their “tour” on the internet. This experiment conceivably has many applications, but is most exciting to me as a pedagogical tool.

One of the highlights of day three was an engaging roundtable discussion on the Anthropocene. In a relatively short time, the idea of the Anthropocene (that humans have changed their environment to such an extent that it qualifies as a new geological era) has achieved a rare public and scholarly resonance. Despite widespread interdisciplinary interest, however, it sometimes seems as if the only thing that people can agree on is that the Anthropocene is a fertile ground for debate. Scholars dispute its beginning (what date, they ask, was the “golden spike” that marked the beginning of the era when humans achieved overwhelming significance in the geological record?), its implications (is it a moral challenge? Social or political? Or simply a new periodization?), and even its existence at all. The panelists of this large roundtable consisted of Christophe Bonneuil of CNRS and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz of the Centre Alexandre Koyré (who coauthored a French-language synthesis of the ongoing contributions of historians to the Anthropocene debate); David Edgerton of King’s College London; Egle Rindzeviciute of Sciences Po; Helmuth Trischler of the Deutsches Museum; and Sverker Sörlin of the Swedish Royal Institute of Technology. Although an entire blog post could consider the perspectives of the presenters, what struck me were two tensions highlighted by the audience. First, the lack of control historians have had over the construction of Anthropocene periodization and the predominant Eurocentrism implicit in its construction. Historians consider themselves the ultimate arbiters (or at least the best qualified analysts) of periodization in the recent geological past. Nevertheless, few scientists consult historians about the temporality of the Anthropocene, either regarding a possible golden spike or as Sörlin pointed out, the importance of the speed of change. Historians have much to offer the discussion, each panelist agreed, but we are equally culpable of perpetuating the narrative of an Anthropocene dominated by Euro-american perspectives. What would an Anthropocene discussion look like if approached by Chinese scholars, for instance? Would they also choose to exclusively highlight issues in European history? What alternatives might others’ find? How might the Anthropocene appear through sub-altern eyes? These questions were left largely on the table, and perhaps better than any other part of the discussion, this demonstrated the necessity for continued attention to this subject.

The final day of the conference featured another roundtable, this time on natural disasters. Discussants included Tim Soens of the University of Antwerp, Bruce Campbell of Queen’s University Belfast, Guido Alfani of the Universita Bocconi Milan, and Eleonora Rohland of the Foundation For Global Sustainability, Zurich/Institute For Advanced Study In the Humanities in Essen. Soens framed the discussion around a new article by social economic historians Bas van Bavel and Daniel Curtis called “Better Understanding Disasters by Better Using History.” The chief arguments of the paper called for greater attention to institutions and social relations as the critical mediating forces in the study of disasters. Only by comparing institutional and social responses to disaster can we hope to gain a better understanding of why some disasters affected certain populations, but not others, in certain regions, but not others, Soens explained. The comparative approach is here critical, and history offers a valuable “laboratory” of events to experiment with. I was familiar with this article, having used the van Bavel/Curtis argument to frame my Posthumus Conference paper on shipworms.

While not without limitations, my own critiques paled in comparison to Campbell who termed the approach “institutional determinism.” Nature and even disaster, he argued, plays second fiddle to the true purpose of van Bavel/Curtis’s argumentation – using disaster to explain institutions. Dynamic nature needs to be one part of eco-socio-cultural model of disaster, but it cannot be universally subsumed within a larger interest in insitutions. My own feelings on the matter fall closer along the lines of the Utrecht school, primarily because it favors regional variability. Neither approach (nor any “model” I’ve come across), however, truly considers the role of disaster perception and the complicated and contingent manner in which disasters affect populations. As interesting as this exchange was, by reacting to one article, the panel left the impression that a huge domain of historical disaster research was being ignored. Alfani offered interesting perspectives on (once again) plague in 17th century Italy, asking whether effective institutions could actually prevent plague. Seemingly the odd woman out, Rohland presented a different vision of disaster research, one grounded in her work on hurricanes, but one that she extended to contemporary discussions of the Anthropocene and climate change. Just as with the Anthropocene panel (and like most good roundtables), this event left the audience with new questions and few, if any, resolutions.

As I left the conference, sweating my way back to the Versailles train station, I couldn’t help but reflect on a (horribly appropriate) paper presented by Richard Keller on the Paris heat wave of 2003. The heat wave was a devastating disaster (killing 70,000 people across Europe) and one worthy of analysis from any number of perspectives, including Campbell’s and van Bavel/Curtis’s (though judging from his focus on social relations, Keller would likely lean towards the Utrecht school). The oppressive July heat during my walk seemed like a fitting confirmation that the study of disasters can sometimes seem frustratingly topical. At the same time, I passed the long avenue leading to the Palace of Versailles, still flooded with tourists despite the weather. During the conference I had taken a biking field trip through the gardens and the Grand Parc beyond. Le Nôtre’s landscaping, I remembered as I walked by, had seemed an almost too-perfect microcosm of environmental history, with its tensions between the power of culture to impose human design and the natural challenges to that ambition. Good conferences linger, I suppose. I am, after all, writing this post on the train, already two countries removed from France. It may have been “too hot to think” at times, but ESEH won’t be over for quite a while.