I’ve been in Holland for more than a week, but up until today, I couldn’t honestly say that my “research” trip had begun. Between conferences, excursions with colleagues, writing lectures, and weekends (when the archives aren’t open), I’ve had little time to do anything else. That changed this week when I was able to visit the Zeeuws Archief in the province of Zeeland. Zeeland is a province of islands-cum-peninsulas. For much of its geological history, Zeeland was disconnected, but over the last several centuries, the Dutch have expanded the boundaries of these islands and linked them together with massive polders. Today, these interconnections appear like gnarled fingers extending out from the southwest of the Netherlands.

Zeeland is the furthest southern maritime province of the Netherlands and during the Golden Age, it was the second most prosperous after Holland. It is also one of the provinces I have the least experience with, having only made one prior research visit and one visit for fun. Luckily, my friends Nick Cunigan (studying at the UvA on a Fulbright grant) and his wife Beth also planned on visiting Zeeland. Nick was planning an archival trip as well and since they were staying with family friends in Middelburg (the capital), I decided to tag along and extend my trip to two days.

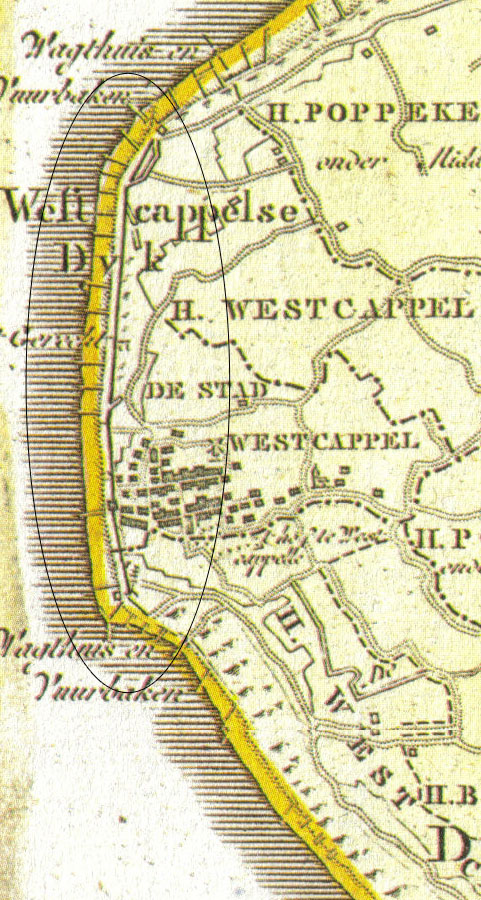

Although archives are often located in or near the places that their documents describe, I am rarely able to both see the historical traces of past places in the archives and then physically step into them on the same day. This was precisely what I did on the Zeeuws island of Walcheren near the village of Westkapelle. Westkapelle, despite it tiny size and relatively modern appearance, has a deep history. It is one of the most western cities in the Netherlands because it is nestled in a nub of Walcheren that extends into the North Sea. The island has changed size and shape over a millennium and is actually the second Westkapelle (the first, called “Old Westkapelle,” was lost in the 14th century and is one of the many “drowned villages” of the Netherlands). The fate of its unlucky predecessor is unsurprising if one considers Westkapelle’s location. The town lies at the intersection of two steep dune ridges that almost meet at the western tip of Walcheren. They don’t quite conjoin however, and in that gap lies Westkapelle. It is a perfect location to tap the wealth and trade opportunities of the North Sea, but it is also incredibly vulnerable to storm surges. I travelled to the archives in Zeeland largely to study this city and its struggle with the sea.

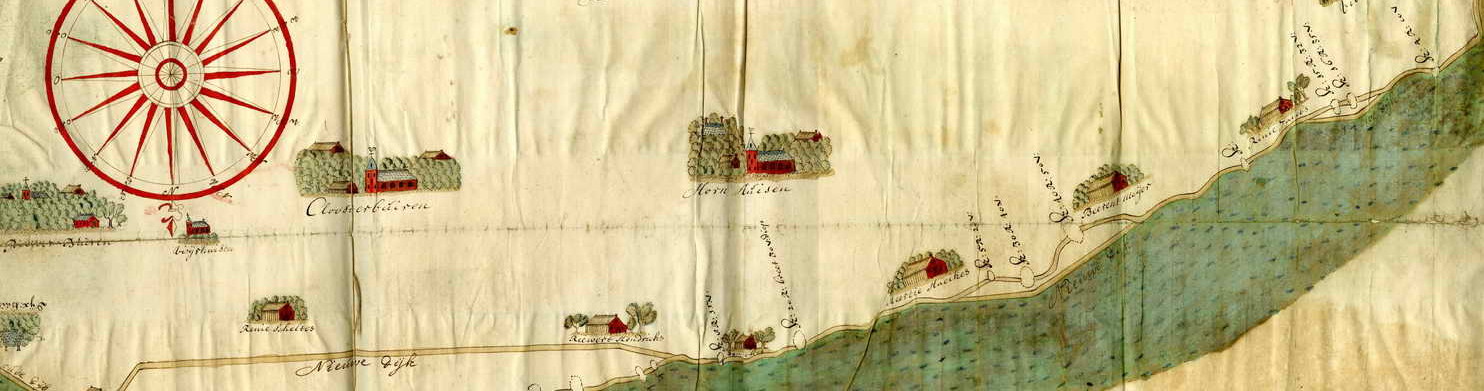

Flooding is without a doubt a formative element of Dutch history and identity. In a country whose wealthiest areas lie below sea level, flooding and flood protection (in particular dikes) are inseparably connected to broader national narratives of Dutch economic success, culture, and even social structure. Dikes protect against the sea, but they are also costly, they require complex communal arrangements to build and maintain, and when they break, they signify a challenge to those same structures needed to erect them. The Westkapelle sea dike is a case study in these challenges. Located at such a vulnerable location, the tip so to speak of the Netherlands, the dike was the vanguard of coastal protection in the early modern period. Although it now appears massive (at “deltahoogte” or a 1/4,000 year change of flooding), the sea dike was much lower in the eighteenth century. It linked the two dune ridges that flanked its northern and southern edges. The dike and its dunes were both highly susceptible to the erosive force of the waves, however, so by the 16th century, inhabitants began building wood, reed, and stone wave breakers to protect the coast. These staketwerken sometimes ran parallel, but on the Westkapelle sea dike also extended out perpendicular to the sea to act as wave breakers (below). A technological achievement in dike protection, these structures were also a fantastic habitat for a new type of biological disaster that hit the Netherlands in the 1730s.

You can see the staketwerken extending westward from the dike likes spikes. From: Tirion/Hatinga, Plattegrond van het eiland Walcheren in de 18e eeuw, 1754

The naval shipworm (Teredo navalis) is a marine mollusk species of unknown geographic origin (called a cryptogenic species) that bores into wooden structures. They spend nearly their entire lives in the tiny caverns they eat into submerged wood and, because they had a particular taste for ships (thus the name), they have been a serious challenge for European mariners since antiquity. They are also a classic fouling species that hitches rides on ships hulls to populate new coastal habitats. Their success and wide distribution prevent any conclusive judgement about their origins, especially since they are only one of several shipworm species and they are difficult to differentiate from other marine borers. Their arrival in the Netherlands was unusually dramatic, however, and the preponderance of documentation about the invasion marks this event as a unique opportunity to study the cultural, technological, and social response to a marine invasive species.

When shipworms arrived in the Netherlands in the fall of 1730, their populations exploded. Not content with ship hulls, they attacked sluice gates, harbor revetments, and sea dike protections like the staketwerken in Westkapelle. Multiple shipworms could infest a single wooden pile driven into the sea, and during storms, the force of the waves would snap the now weakened wood. Zeeland was not the only province to employ wooden wave breakers, and dike inspectors throughout the coastal Netherlands discovered similar infestations in their own constructions. People panicked. They wrote religious treatises condemning the arrival of the “worm” as a punishment sent from God, they wrote natural historical treatises on the species, and dike engineers experimented with new shipworm-proof dike designs. Ultimately, the shipworm epidemic touch off a fundamental redesign of dikes throughout the coastal Netherlands.

Under-girding much of this response were several basic questions. Why did the shipworms appear? Why were they in certain places, but not others, and why did they appear at the particular time they did? I investigated these questions both from a modern and eighteenth-century perspective in my dissertation in the context of Holland, but I wanted a comparative study. Zeeland, and the Westkapelle sea dike in particular, was perfect because it was the location of the first known outbreak.

Shipworms thrive within a defined set of ecological limits, the most important of which are salinity, temperature, and habitat availability. I had already dealt with issues of temperature and salinity in the past using GIS in a separate project, but a new element I’ve begun investigating is their habitat. Shipworms did not infest all wooden structures on the coasts of the Netherlands, they didn’t even affect all of the wood in those areas with suitable salinity and temperature. Infestations clustered around large ports with contacts to the tropics (evidence I have taken to justify their invasive origin). This explains their location, but it doesn’t explain the timing. Why in the 1730s and not before? Drought was likely a part of the answer. The early 1730s were unusually dry and the reduced river output would have heightened salinity and created more ideal breeding areas for the mollusks.

The 1730s were not the only drought period since ships began returning from the tropics, however. Why didn’t shipworms appear during these earlier era of low river output? I suspect that the answer probably lays in a combination of environmental and human factors, including the expansion of their wooden habitat. Staketwerken in Zeeland, paaldijken (a sort of wooden palisade that fronts dikes in Holland), and wierdijken (a wood and seagrass construction) in West Friesland) would have been ideal habitats for these wood-boring mollusks. Unfortunately, each of these dike constructions predated the shipworms by centuries. What is unclear is the scale at which they were built. Were these structures only used to reinforce the most vulnerable areas of the coastal Netherlands, an thus only offering limited habitat? Their expense demanded vast resources, and since the half century leading up to the 1730s was a period of relative economic stagnation in the Netherlands, they would not have been built without serious need. Money was the principle limiting factor for the expansion of these protections, and as a result, also a limiting factor for shipworms.

Shipworms pictured in Holland next to harbor revetments. Dike workers are shown removing the infested wooden piles.Paalwormen die de dijkbeschoeiïngen aantasten, 1731, Abraham Zeeman, 1731 – 1733

This same period also witnessed accelerating ecological changes, however. The shifting dunes of Walcheren (a serious problem in the 1720s) and the erosion of land in front of dikes (a serious problem in shipworm-infested West Friesland and on Walcheren) expanded the vulnerability of these regions. The Dutch would have found themselves in the awkward position of needing to drastically expand their system of coastal protection (what Petra van Dam refers to as the “hardening” the land-sea border) while at the same time having limited financial means to do so.

Where will this line of research take me from here? Two directions. First, I will map out the potential habitat for affected regions of the Netherlands. Where exactly were the coastal regions of the Netherlands affected by shipworms? Contemporary maps sometimes contain this information, which I can then digitize and integrate into a larger model of shipworm suitability that includes salinity. I will also try to tease out how the Dutch on Walcheren, as well as other regions, managed to negotiate this difficult economic/environmental situation in which they found themselves by the 1730s. Did they expand their use of wood? If so, by how much? These are difficult questions, but the trip to Walcheren was the first step.

That step included literally walking on the now asphalt coated Westkapelle sea dike. It’s now massive and one can barely see the lighthouse in the city from the other side of the dike. It seems an impenetrable barrier and its easy to forget how recent this monumental new iteration of the sea dike actually is. At the end of my first day in the archives, I was excited to finally see the dike I’d been reading about. What I couldn’t have expected was that everything about this area belies its past. It is now a resort town. Dutch and German vacationers sun themselves on the beach (though obviously not on the cloudy day that I visited) and surfers swim out from shore to catch remarkably low waves. Driving through the modern Westkapelle village (while catching a brass band play the Band of Brothers theme song at a public concert), its easy to forget that this now quaint seaside village was once the site of a massive invasion. This history is now buried in the dikes. Before I left, though, I looked out to shore and noticed some dark shapes in the water. It was high tide, but appearing intermittently between the cresting waters, were large wooden piles. Westkapelle still uses wave breakers. I would only have to wait until low tide. With patience, I would see them.