Resilience is the new buzzword for historians who study disaster. How do societies respond to adverse weather, disease, or warfare? What conditions prompt successful rebounding from catastrophe? How can one measure the differences between one group of peoples’ responses from another? These questions drive the sub-field and the many recent publications, conference panels, new research groups, and the workshop which is the subject of this post demonstrate its growing vogue.

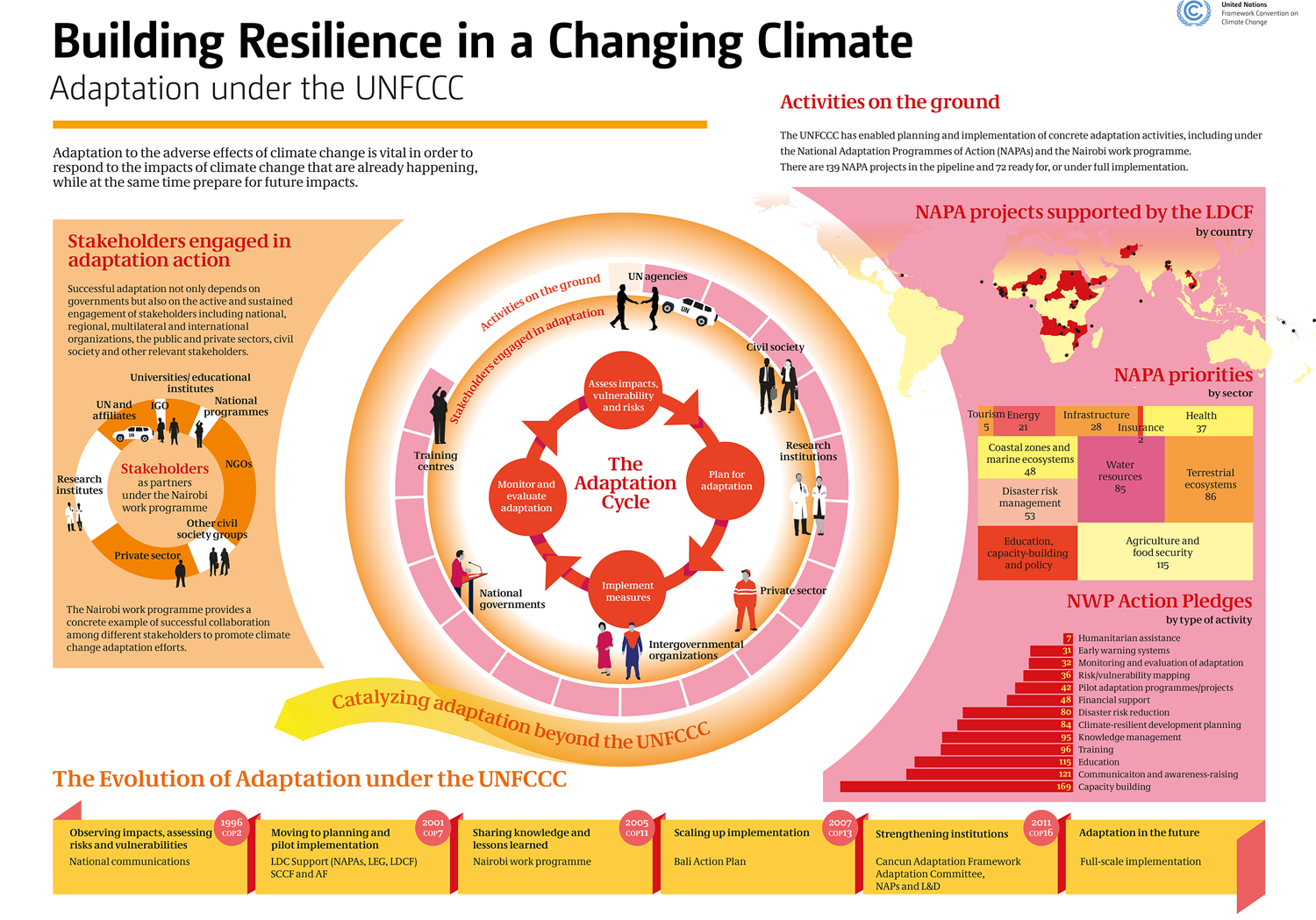

Although disaster history is a relatively new field, having only come into its own over the past ten to fifteen years, it had already witnessed the rise and fall of several similar terms that promised to unify the field under a common set of goals, themes, or subjects. Adaptation (and adaptive capacity), vulnerability and risk, and memory have each enjoyed their moment in the sun and to a greater or lesser extent, continue to exert influence on the field. The current focus on resilience follows in a similar vein by drawing explicitly on social scientific and contemporary policy concerns.

Disaster research (including historical) tends to follow trends in policy. Climate policy in particular has driven the push for greater attention to resilience in research.

In particular, resilience scholarship promises to offer new interpretations on how past societies created durable and sustainable social, technological, or cultural relationships in the context of environmental change. The relationship between resilience and “sustainability” (an even more powerful and politically resonant buzzword) can also offer interesting and valuable insights into modern problems associated with disaster and sustainability. Look to past, the proponents of this subject argue, for models for future behavior. As a result, it is not unusual to see resilience-oriented studies pop up in the context of larger initiatives focused on issues of sustainability, both in policy-relevant contemporary contexts and in history. The Rijksuniversiteit Groningen’s research group “Sustainable Societies: Past and Present,” for example, is housed in the Research Centre for Historical Studies and grounded in a similar ambition.

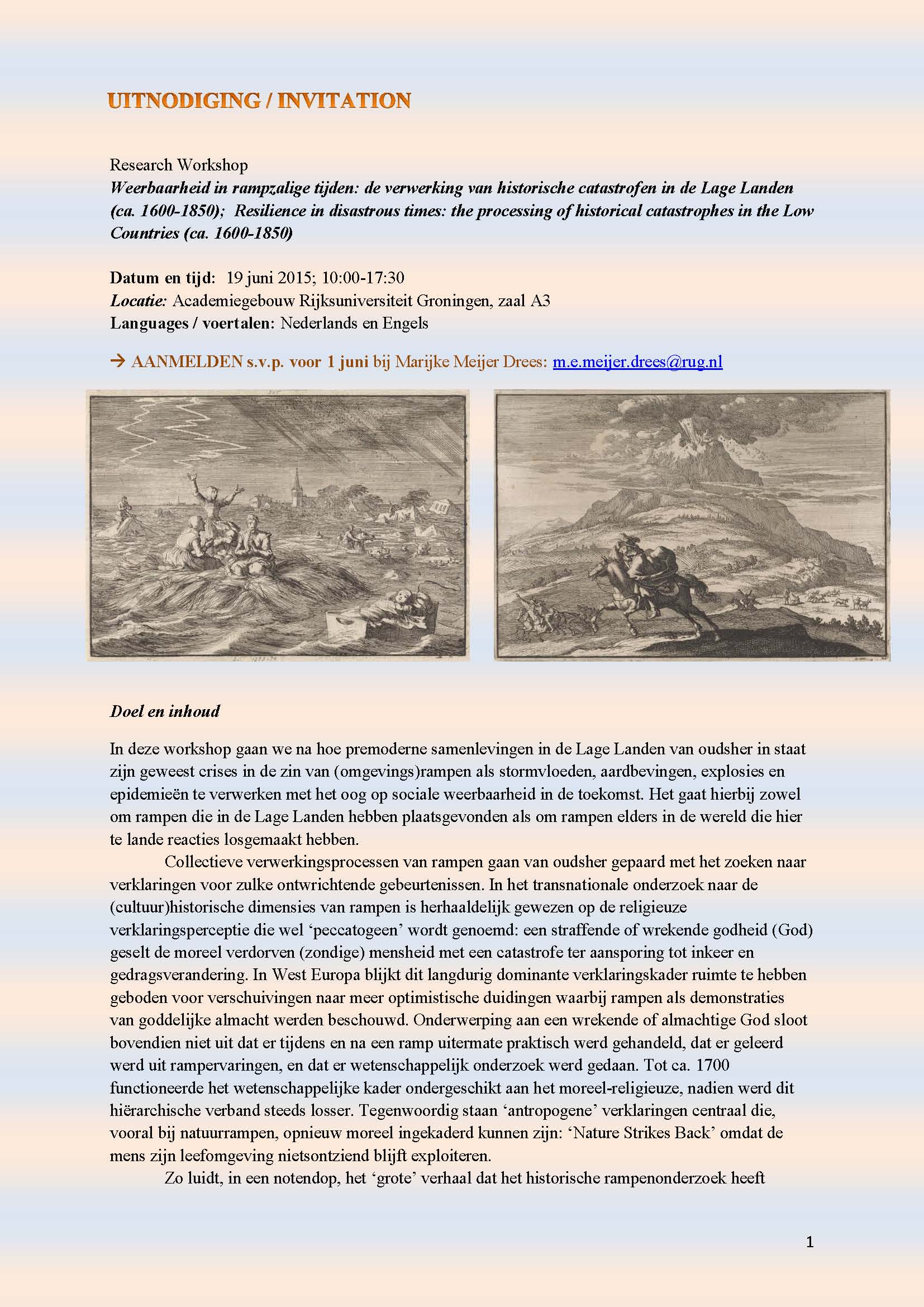

Resilience has not been an important element of my research in the past, although the cultural and technological response to nature-induced disasters is a central element of my dissertation. Partly, this is because the same conditions that make “resilience” such an engaging buzzword (i.e. its policy-relevant, modern, economic and social characteristics) make it a difficult term to adapt in premodern times. Rather than tackle the subject head on, I dealt with constituent elements that I could more easily harness (like memory and learning from disasters). As a result, I completed the project on schedule (my primarily goal all along), but my failure to examine disasters in way that explicitly offers useful lessons for disasters in the present has always been rather disappointing. This is why I was intrigued by the invitation to present my research at a workshop called “Resilience in disastrous times: the processing of historical catastrophes in the Low Countries (ca. 1600-1850)” at the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen (RUG).

The workshop promised to examine resilience (weerbaarheid) from a cultural context. How did people write about disasters and could those writings also work as coping strategies? How were disasters remembered, or mis-remembered? What types of media conveyed that information? What dialogues did people employ to explain disaster? Finally, and perhaps most importantly, how did each of these ways of interpreting the culture of disaster accommodate or determine the practicalities of bouncing back from catastrophe? This last point was of particular importance to me. Cultural history is saddled with the (in my opinion) undeserved reputation of seeming unanalytical, vague, and impressionistic. Cultural history can also work in a realm beyond description, and I try in my work to use culture as both context and the driver of social, technological, and even environmental change.

Presenters came primarily from the RUG, with myself, Lotte Jensen from Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen and Petra van Dam of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam excepted. A number of research masters and PhD students as well as other faculty joined the conversation as well. We would each have about 30 minutes for presentation and discussion of our work. There would be a welcome by one of the co-organizers Marijke Meijer Drees as well as opening and closing remarks.

Although resilience is a popular subject in disaster scholarship, one cannot make a similar judgment in the context of the Netherlands. Disaster scholarship is a strong field in Germany and Switzerland, the introductory speaker Raingard Esser noted, but Dutch scholarship largely lacks a similar history of involvement. Although Dutch history has been punctuated by persistent (sometimes catastrophic) disasters, and although many historians acknowledge the cultural power of (in particular) flooding, catastrophe does not occupy a position of cultural force in Dutch scholarship. This has always seemed somewhat surprising to me. Disaster has played a prominent role in the Netherlands’ strong traditions of social and economic history, as well as historical geography. Of the few environmental historians working in the Netherlands, several of them specialize in disaster or disaster-related fields as well. That said, the study of historical disaster & culture is underdeveloped. That this workshop happened at all may be a good indication that times are changing.

Each of the speakers offered fascinating glimpses into the history of Dutch disasters, stretching from the medieval past to the 19th century. Following Esser’s introductory framing of cultural disaster history, Drees presented her work on continuity and change across disaster narratives, particularly in the context of poetry. She highlighted several different types of disasters (and unlike many other presenters) included different geographic regions, for instance the London Fire (1666) and the Delft Gunpowder Explosion (1654). What was fascinating to me was the manner in which Dutch observers not only recycled literary themes, but also visual themes int their disaster print making – showing again the power of this type of cultural inertia.

Each of the speakers offered fascinating glimpses into the history of Dutch disasters, stretching from the medieval past to the 19th century. Following Esser’s introductory framing of cultural disaster history, Drees presented her work on continuity and change across disaster narratives, particularly in the context of poetry. She highlighted several different types of disasters (and unlike many other presenters) included different geographic regions, for instance the London Fire (1666) and the Delft Gunpowder Explosion (1654). What was fascinating to me was the manner in which Dutch observers not only recycled literary themes, but also visual themes int their disaster print making – showing again the power of this type of cultural inertia.

Joop Koopmans followed Drees with his own preliminary work on the shipworm epidemic and media response. He focused primarily on Dutch newspapers and employed the new Delpher tool with the KB to great effect. Delpher is an ongoing digitization initiative at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague. It allows remote users to access full-text copies of Dutch periodicals, books, as well as newspapers going back to the 17th century. His work was particularly helpful for me, not only because we both presented on shipworms, but because his focus on the media impressions of the worms was a subject I had never explicitly dealt with. Following the lunch break, I presented my own work on the shipworm epidemic of the 1730s, in particular it role as a novel biological invasive. I argued this novelty was a crucial explanatory variable that helped explain the decision-making process.

Lotte Jensen followed the pair of shipworm presentations with her own work on disasters and collective identity fashioning in the era of Louis Napoleon (1806-1810). She argued that news accounts and visual images used disasters to either boost the popularity of the French King or denounce the French occupation. Finally, Petra van Dam presented work on the disaster relief efforts in the wake of the river floods of the 19th century. She also worked in the context of Dutch newspapers and archival material and investigated the meaning of lists of relief donations and lotteries. She found that there were profound continuities between the cultures of relief action in the past into the 19th century, particularly their relationship to established (religious) aid organizations.

The workshop was a fascinating break from the type of research agenda I’ve had in the past. I have never been to a Dutch workshop and its informality, welcoming nature, and (of course) the borreltje at the end fostered a warm and inviting atmosphere. It was also a fascinating intellectual exercise, particularly because the cultural context of Dutch disaster is so little understood. What would be truly interesting is to compare the findings of this workshop with work from other areas in Europe or around the world that have enjoyed greater attention to the culture of disaster in their scholarship. The mystique of early modern Dutch history has always been grounded in some recognition (albeit highly contested) of Dutch exceptionality. But was there something truly unique about Dutch cultural response to disaster? This question will have to be left to future workshops with a more comparative bent. In the meantime, perhaps this event is a hint that we might expect a greater interest and participation in historical disaster studies and culture in future.