Dikes, dams, and culverts. These were the themes of the recent conference sponsored by the Stichting voor de Middeleeuwse Archeologie (Association for Medieval Archaeology). The organizers laid out a short, one-day conference featuring recent archeological, historical, and geographic research on the subject of water management and water defense. Papers spanned a broad period of time, from Roman era dikes in Zeeland to ongoing efforts by the Rijksdienst voor Culturele Erfgoed (Institute for Cultural Heritage) to manage and protect dikes today and in the future.

Hosted by Archeologie West-Friesland and MC-ed by the inimitable Michiel Bartels, the conference took place in the port town of Hoorn in Northern Holland. A former trade headquarters for the VOC (Dutch East India Trading Company), the city boasts a fantastic history and a well-preserved city center that hugs the west coast of the former Zuiderzee. Unlike many similar-sized cities in the Netherlands, Hoorn’s former wealth (generated during the 17th century Golden Age) remains on full display. The conference location, the impressive Oosterkerk, is evidence of this past.

The conference itself showcased recent scholarship conducted on Dutch (and northern German) dikes. It also served as a sort of context for the publication of a new multi-volume book called Dwars door de Dijken (“Straight through the Dikes”). This book is a comprehensive account of recent research into West Frisian dikes and dike ecosystems (including both environmental ecosystems as well as the structures and landscape features that typically accompany coastal dikes such as sluices, dijkmagazijnen, voorland, etc.). The book is an impressive interdisciplinary collection that documents over half a decade of research made possible through the cooperation of numerous parties, including the Stichting voor the Middeleeuwse Archeologie, Hoogheemraadschap Noorderkwartier, Stichting Archeologie West Friesland, and the municipality of Hoorn.

The conference featured a wide variety of disciplines and specializations. Petra van Dam kicked off the event with a thoughtful consideration of the role of dikes and other adaptive measures that tended to limit flood fatalities in the middle ages. Working on themes framed by her work on the amfibische cultuur, Van Dam noted the importance of early warning systems, fleeing to high ground, and compartmentalization of the landscape to slow the advance of inundation. These cultural adaptations to flooding were key strategies, Van Dam maintained, that medieval inhabitants of coastal regions and floodplains used to mitigate disaster.

One of the most compelling presentations was by Seger van der Brink. A geologist and maritime archeologist, Van der Brink presented the fascinating case of the “verdronken dijk van Texel.” Using sidescan sonar, an acoustic technique of visualizing the sea bottom, Van der Brink and his team discovered the remains of what appeared to be large rectilinear form under the Marsdiep approximately 600 meters from the shore of the North Holland island Texel.

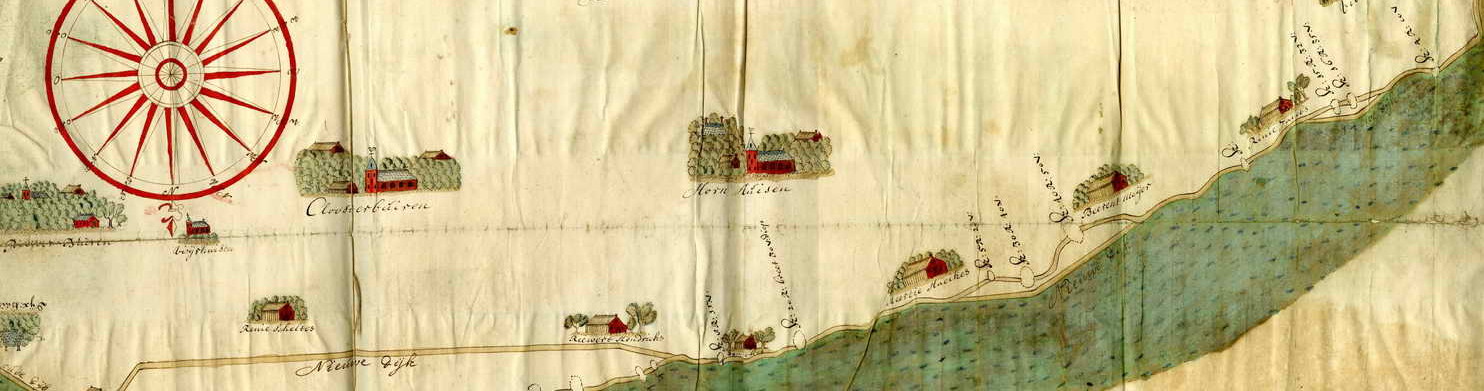

The “drowned dike of Texel” Kaart van het Horntje, Mattijs den Berger, 1751: http://tresor.tudelft.nl/kaarten/webpages/TRL_12_1_2_17.html

Van der Brink presented this case almost as if it were a detective story, beginning with the accidental discovery of the anomaly, followed by historical cartographic evidence (sadly no documentary evidence), finally revealing its identity as a dike constructed in 1749 and reinforced with stone (likely a result of the “petrification” of the Zuiderzee coastline due to the shipworm). The dike disappeared in 1792 as a result of the changing dynamics of the Marsdiep, though sadly, the story of the dike’s disappearance was not a central element of the talk. Nevertheless, the dike is the largest underwater find in the Netherlands and was an impressive showcase of recent work in maritime archeology.

Luuk Koenen, from the independent archaeological firm RAAP spoke about recent excavations of a dike along the Waal River to the north of Nijmegen. Aside from research into the structure of the river dike, RAAP is also conducting historical-geographic information about landscape use and landownership using documentary data. Sander Gerritsen presented a very animated and enjoyable talk about Archeology West Friesland’s excavation of the Klamdijk (the same dike I visited last year) and Robert van Dierendonck presented findings on three different ancient and medieval dikes in Zeeland.

The keynote address was shared by three German archaeologists: Sonja König from the Ostfriesische Landschaft Archäologischer Dienst and Anette Siegmüller and Johannes Ey from the Niedersächsischen Instituts für historische Küstenforschung. Their presentation reconstructed the dike profile of a paaldijk near the Eems river close to the border of the Netherlands in the Dollard region. I had known that German and Dutch dikes often shared certain characteristics. Dikes are like extended families. Close relationships seem to follow geographic proximity, but (because of information networks) dikes in regions far from one another remain “cousins,” sharing notable features. Paaldijken are a case in point. Some coastal dikes in the Dollard region in German used long palisade-style wooden constructions to protect the earthen portion of the dikes from the force of waves. These were likewise employed in Friesland and the Zuiderzee region (now the IJsselmeer). König, Siegmüller, and Ey’s presentation laid out the historical development of this dike from a minor embankment to the modern construction one can visit today.

Two points were of particular consequence for me: first, that this paaldijk was not infected by shipworms. This is to be expected in an area bordering the Eems. Shipworms avoid areas with low salinity like the mouths of rivers. Shipworms did not make an appearance in Groningen (across the border in the Netherlands) until well after the initial outbreak in the 1730s. That said, they would eventually infest the Dollard region, even popping up near the town of Delfzijl. It would be interesting to determine whether similar paaldijken were constructed further from the Eems river, and thus more susceptible to infestation.

The second point related to the Christmas Flood of 1717, a massively destructive early modern disaster which devastated large areas of the northern German and northern Dutch coastlines. Jarssum’s paaldijk was likewise affected. Using historical sources (in particular cartographic material), the presenters showed

Homann’s map of the inundated regions of the Southern Sea and Wadden sea areas (in brown). Geographische Vorstellung der jämmerlichen WASSER-FLUTT in NIEDERTEUTSCHLAND, welche den 25.Dec. Ao. 1717, in der heiligen Christ-Nacht, mit unzählichen Schaden und Verlust vieler tausend Menschen einen großen theil derer Hertzogth. HOLSTEIN und BREMEN, die Grafsch. OLDENBURG, FRISLANDT, GRÖNINGEN und NORT-HOLLAND überschwemmet hat. Source: http://www.ich-war-hier.de/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/P1040061.jpg

damaged caused by the Weihnachtsflut and its subsequent repair. Contemporary German and Dutch sources often reference the use of ships to block the largest dike breaches and contemporary maps of the disaster actually show these ships on the maps themselves! Johann Baptiste Homann’s 1718 map of the Christmas Flood is perhaps the best-known example and it likewise depicts these iconic ships.

To my knowledge, little scholarship exists on this fascinating source material. Although maps are often used in historical research (and apparently even MORE frequently in archaeology), disaster cartography, especially from the early modern period, is underdeveloped. This presentation provided further confirmation that more research into this subject is necessary.

The second half of the conference tended to focus on the early modern and modern, rather than the medieval past. Menne Kosian of the Rijksdienst Cultureel Erfgoed gave a general overview of what he termed the “schizophrenic” relationship between the Dutch and water. My own presentation covered the first phase of the shipworms epidemic between 1730-33 through the lens of “causal storytelling” (see blog for transcript) and Miranda de Wit of the engineering bureau MUG laid out her findings related to a 17th-18th century sluice in Drenthe. The final two presentations brought us into the modern period. The final two presentations were less historical or archaeological case studies, than “state of the field” talks. Michel Lascaris of the Rijksdienst Cultureel Erfgoed in Amersfoort and Michiel Bartels of Archeologie West-Friesland showed the audience the two faces of dikes as cultural heritage. On the one hand, dikes are living relics of the past. They reveal changing patterns of spatial development and settlement; they are artifacts of disasters and demographic changes; and they are material evidence of the historic relationship between humanity and the environment. Dikes, in other words, are archives. Dikes are also water protection, however. They are a necessary boundary between the sea and an (increasingly) vulnerable population. Lascaris and Bartels showcased the cultural value of dikes by highlighting their diversity and the special challenges cultural heritage and archaeological organizations face when attempting to use, explore, promote, and protect these unique structures.

In the final panel presentation, which featured Van Dam, Bartels, Lascaris, Keunen, and Van den Brink, the audience was offered the opportunity to comment on some of the larger questions addressed over the course of the day (and some that weren’t). Of particular interest to me were Van Dam’s comments about the importance of storytelling in the context of dikes. Drawing a distinction between archeological and historical scholarship, Van Dam made the case for argument and narrative as compelling components of dike research. From my own perspective is seems clear that dikes are more than just the physical remnants of past settlement. Dikes tell stories. They can reveal tragedies and showcase hubris.

Today, the historical value of dikes tends to be ignored by the public. Few actively recognize their ongoing use as water defense, leaving the job of managing their vulnerability to elected officials and engineers. Landowners may consider them barriers or obstructions (thus necessitating the official protections that conserve historically significant dikes like the Westfries Omringdijk). Even people who regularly use dikes for roads or recreation are frequently unaware of the history of these structures. This is where archeology, history, and historical geography have their greatest opportunity.

Last summer’s “open dike day” near Hoorn was very well attended by the public. Standing in the audience, people seemed to be fascinated by the process of discovery. They marveled at the depth of the excavation, and how the archaeologists pieced together the history of the structure with artifacts, historical documents and maps, and the guts of the dike itself. They were also interested, however, in the story of the dike. This included, of course, its historical story. The historical dispute that gave the Klamdijk its name, for instance, or its history of flooding and repair. Likewise, it also included the story of its future. Representatives of the local water board were on hand to discuss why a new pumping station (that opened up the possibility of excavating this protected space in the first place) was necessary in a climate changed future. The Open Dike day had cleverly married three stories: the story of the dikes past, the story of that history’s discovery, and the story of a potential future. Several of the presentations from Dijken, Dammen en Duikers likewise told stories. Grounded in evidence, they both engaged the public and inspired further questioning. Taken as a whole, the conference did so as well. The coda to this conference was the public unveiling of Dwars door de Dijk. My hope is that this work, like the conference it concluded, serves as a bridge between disciplines and between publics. Dikes appeal to a number of metaphors, and perhaps that blunt involve allusions to separateness, compartmentalization, and division. But as Roos van Oosten, the chairwoman of the Stichting Middeleeuwse Archeologie, also noted in her introductory remarks, dikes have in the past been the embodiment of cooperation and productive communal ambition. It was a fitting conclusion, I thought, that Van Oosten returned to this image and this same spirit (this time in the context of scholarship) at the closing of the conference.