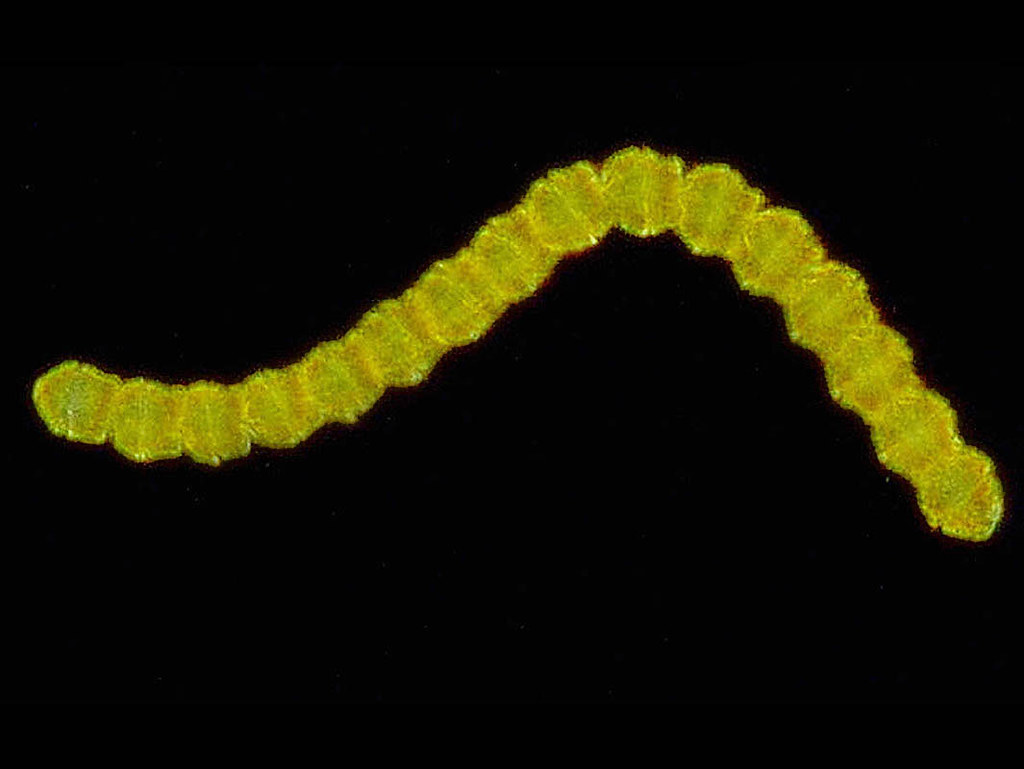

Ballast water is broadly understood today to be an important driver of marine and aquatic introductions worldwide, and it is thus subject to multiple regional, national, and international regulations. In the mid-1980s, however, marine “bioinvasion” science was nascent and management nearly non-existent. A series of dramatic and consequential introductions in the mid to late 1980s catalyzed this change, including the discovery of novel algae species (called dinoflagellates) in Australian waters. Several species produce toxins that, when filtered through shellfish and ingested by consumers, can result in “paralytic shellfish poisoning.” One such species (Gymnodinium catenatum) was discovered by chance in 1985/6 after it bloomed into a red tide near the marine research station in Hobart, Tasmania. Its proximity to nearby shellfish aquaculture farms, was enough to spark a short lived public health scare. More importantly, it generated sustained interest and resources into the source of the scare. Where had these algae, which had never been detected in the Southern Hemisphere, come from?

Scientists quickly suspected that the species was introduced in the ballast water of bulk carriers that shipped woodchips from Tasmania to markets in Japan. Like aquaculture, woodchip exports were growing during the 1970s and 1980s, the latter to feed Japan’s postwar boom in pulp and paper manufacturing. The resulting trade simultaneously exported Australia’s forest and marine resources abroad, invited unanticipated species introductions in return, and transformed phytoplankton into a public health hazard. This discovery catalyzed new scientific studies and focused public policy on ballast water management. By 1990, the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service produced ballast water guidelines, which provided a template for later international ballast water management strategies – among the most significant global tools to limit the unintentional transfer of species.

This, in a nutshell, is the story I’m working to flesh out and explore for the next three months while on sabbatical at the National Library of Australia in Canberra. Some of it is already well known, especially among marine scientists, but virtually nobody has tackled this subject from the perspective of environmental history, or the history of science. And like every good story, it provokes as many questions as it seems to resolve.

- Why Tasmania? Toxic dinoflagellates were merely the first in a long list of problematic “invasives” to affect marine and aquatic habitats in the 1980s and 1990s. Was this region uniquely susceptible? If so, was it due to environmental or social reasons? Or was it merely observer bias? (CSIRO has a Marine Research laboratory in Hobart and aquaculture and fishing are primary industries)

- Why woodchips? Woodchip ships seem to have been implicated in ballast water introductions in a number of locations around the world in the 1980s. Was this yet another artifact of observer bias (scientists just happened to be studying the places where woodchip ships frequented), was it an aspect of ship design? Something else?

- Why Australia? Australia quickly vaulted to world leadership in ballast water science and management in the 1980s and 1990s. They were certainly not the only state facing novel marine challenges during this period. What conditions promoted scientific and policy innovation?

- What about the public? How much influence did the broader public play in any of these changes? How did they respond to public health warnings of toxic shellfish. Were they concerned about economic impacts? Australia seems to have avoided some of the worst impacts of Red Tides/PSP experienced elsewhere (mass sickness/death, consumer fear and industry losses) – what generated the political will?

- What about the environmentalists? Tasmania was a hotbed of environmental activism in the 1980s, and much of their attention focused on woodchipping and the possible environmental impacts of pulp and paper processing on the island. Their concerns mostly focused on pollutants like dioxin, but the linking of ballast water mediated introductions to woodchip ships from Japan would seem to be an easy supplement to their list of harms. Did they grab this low hanging fruit?

The library hosts a wonderful collection of primary and secondary sources, including ecological baseline studies, ballast water studies, historical newspapers, environmental impact statements, and more. I’ll also be interviewing scientists and policymakers who participated in the development of ballast water science and management.

This is a new direction for my research program. My first book investigated European natural disasters, including marine bioinvasions. My second book project explores the history of maritime expansion, species introductions, and their relationship to emerging global environmental ideas since 1600. My work at the NLA will form the basis of its final section, which covers the environmental history of postwar biotic “disasters”, the influence of science and industry in ballast policies, and their connection to global environmentalism.