Have you ever seen inside a dike? After studying the history of Dutch dike building and design for some years now, I imagined something quite simple. Early modern design proposals and diagrams of dikes were common currency by the 18th century. Some focused on the dike bodies themselves, others showed the construction of protective revetments. While a few look inside the earthen dike body themselves, one is left with the impression that those constructions are precisely what one would expect, a core of sand or earth with successive layers of additional material pile d on top as necessity demanded. I have also come across a small number of diagrams from archaeologists who unearthed those layers, but they were few and far between.

Dikes in the Netherlands have a timeless quality to them. Despite their obvious connections to human management, they seem an almost natural part of the landscape. They’re a fundamental component of what the Dutch refer to as their “cultural landscape,” an environment intimately connected and, in fact, largely crafted out of human design. Dikes give order and structure to many cultural landscapes in the Netherlands and one of the oldest and best preserved regions that demonstrate this fact is West Friesland.

West Friesland lies in the current province of North Holland. Formerly a vast expanse of inland lakes and peat bogs, it is now a fertile (albeit still somewhat amphibious) medley of polders (drained remnants of former lakes), farmland, villages, and seaside towns. In a sense, it evokes the idyllic pastoral scenescape foreigners like me envision when they imagine the Netherlands. Sheep graze on green grass, small ditches create a charming checkerboard pattern of the landscape, and a few extant windmills round out the view. Hardly buried beneath this veneer, however, is a landscape equally derivative of disaster, social tension, and the struggle to manage the limits of an increasingly vulnerable landscape.

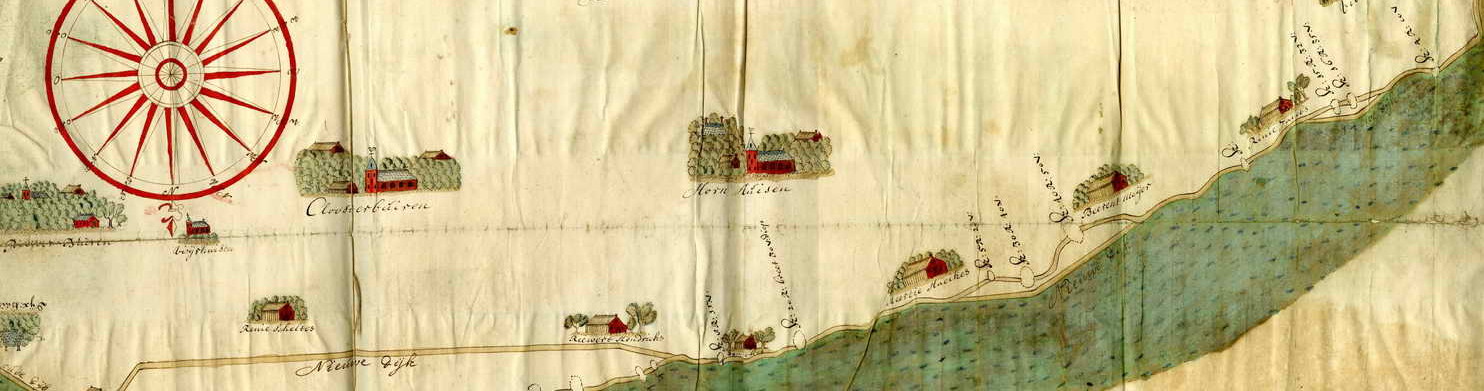

The central feature of the West Frisian cultural landscape is the Westfries Omringdijk, a large “encircling dike” that stretches 126 kilometers around the polder landscapes between the towns of Alkmaar, Hoorn, and Enkhuizen. Built over the span of centuries by connecting smaller dikes, it is a remnant of medieval, early modern, and modern dike techniques. The dike is a considered a cultural treasure (and a provincial monument) and is one of the few such dikes of such cultural significance.

Despite their importance as a repository of historical and cultural meaning, dikes are an understudied subject in the Netherlands. I was dumbfounded when Robert van Heeringen, an established archaeologist visiting the dig, explained to me that relatively few dikes have been completely excavated and a science on this subject has only recently developed. This state of affairs can partly be explained by their ubiquity no doubt. Dikes, particularly in the western third of the Netherlands and in the river lands, are virtually everywhere. Many of them are also still necessary components of local and regional flood defense. One cannot simply remove a section of interesting dike for study (one can’t do this anyway because of regulations prohibiting the removal of large amounts of earth in Holland). This explains my excitement when Michiel Bartels, a senior archaeologist in West Friesland invited me to an “Open Dike Day” near the town of Schardam.

I wouldn’t just see inside a dike, he promised, I would stand inside one. “What size boots do you need,” he asked? I had brought my own, but the opportunity to literally “get my boots muddy” (as Don Worster used to counsel his students) was fantastic. Historians don’t typically get to see, much less stand in the subjects of their research, though as environmental historians, we’re encouraged to take every opportunity to do so. This was my chance. I would meet Bartels at the West Frisian archive and then he would drive me to the dig.

The opportunity to dig a cross section into a dike only comes along rarely. In West Friesland, archaeologists had already completed a dig near the town of Medemblik to the north, but opportunities generally arise only once every few years. The open dike day would feature a new dig made possible because the Hoogheemraadschap Noorderkwartier (water board of the north of Holland) planned to construct a new pumping station near Schardam. The dig site was called Lutjeschardam (little Schardam) because of the presence (seen on old maps) of a tiny village of the same name nearby. The village no longer exists and Bartels speculated that there may be evidence of the settlement set inland from the dike. Hopefully, he said, there would be an opportunity in the future to investigate the area, but it was not on the immediate agenda.

The dike itself was fascinating, partly because of its technological history and partly due to its social history. Land in front of the dike (called voorland) had continually eroded away over the course of centuries so that by 1298, the Holland nobleman Floris V instigated the process that would create the encircling Omringdijk. This was necessary because the increasing water level had combined with the sinking land in the area to increase flood risks. Many scholars term this process oxidation, but in fact, it’s a different process. When water is drained from a peat landscape, the resulting conditions increase the microbial activity in the peat, degrading it, which in combination with the increasing pressure from earth above, compacts the soil. This transformation is ongoing today and water authorities continually fight against these long term landscape changes.

One section of the original Omringdijk was the dike section at Lutjeschardam, which if you look at old maps, is referred to sometimes as the Clamdijk. “Clam” in this case referring to conflict. As more and more land disappeared, the ring dike shifted inward and the Clamdijk was no longer a critical component of sea defense. In the middle ages, tension developed between the two water boards and their inhabitants who refused to pay for its upkeep. Eventually, the count of Holland was called in to mediate the dispute and he ruled that the waterboard of Drechterland (within the Omringdijk) was responsible because the Clamdijk had historically been a part of the encircling dike. History was a crucial component in these types of disputes and the heritage of the conflict lived on in its name.

The dike itself was the outcome of centuries of maintenance and expansion. It was a remarkably broad dike although it did not abut the sea. The cross section, excavated in a terrace-style manner, revealed layers upon layers of new additions. The core of the dike, Bartels explained to a local TV crew in the early afternoon, was constructed of clay and peat and stomped down by people and sleds, compacting it. Layers upon layers would be added later as the dike’s use changed. By the 17th century, inhabitants had begun adding debris to the mix, so you see a variety of odd pottery sherds, broken tobacco pipes, and animal bones. One of the volunteers helping clean the material showed me a pot sherd that originally came from Portugal. Portuguese salt was an important import because it was needed to salt Dutch fish (particularly herring) for domestic and international consumption. The white Portuguese salt pots with decorative blue glaze eventually found their way into the dike as well. Earth is a prized commodity in a region where land sinks or erodes away, so it makes sense to fill gaps with whatever material becomes available.

Perhaps the most unique feature of the dig was the evidence of an early flood and dike doorbraak (break through). When dike breaches occurred, Dutch engineers employed a variety of efforts to reconstruct them, including sometimes sinking ships laden with stones in the breaches to plug the hole. Dike breaches occurred frequently in West Friesland and the winding trajectory of the dike in combination with what look today to be small lakes behind those curves is actually historical evidence of past disasters. When water overtops a dike, it scoured away the land immediately behind it (called a wiel). Today, if you ride on the bike path along the dike, you can read evidence of the disastrous past in the landscape itself. Back at Lutjeschardam, one of the project managers for the pumping station project joked that he was glad no ships had been found in the doorbraak because unless they “were made of gold,” it would have slowed the excavation and become a real problem for their timeline.

The only current pumping stations are on the northern and southern tips of the hoogheemraadschap, visualized in this map of water storage districts. The new station at Lutjescardam will be mid way up the region.

As the pumping project develops, this landscape will be irrevocably changed. In a sense this is unfortunate. This portion of cultural heritage will no longer retain its continuity. On the other hand, this open dike day would likely not have been possible without the construction. Archaeology West Friesland works hard (and incredibly fast) to excavate and understand these dikes when opportunities arise and this dig offered important new information for them. One might even conceive of this new pumping station as a fitting part of the larger history of this dike, always evolving with new technologies and new environmental conditions. This pumping station will be an important new element of water management in Holland because only two other stations in the entire region pump water out of the polders. At the same time, in a climate change future marked by rising seas and increasing likelihood of droughts in Holland, the pump can work in reverse to ensure that high value agriculture (like the tulip fields in the north) will have adequate water. The water board is planning far into the future, but at the same time, allowing scholars the opportunity to gain a clearer picture of the past.

orical relations with that broad region” would be too restrictive in a field that seems to be reinventing itself to be the most global of historical disciplines. Thoen and Soens stressed that the journal would accept submissions from other regions as well, though this didn’t placate the audience. The journal has already taken leap in the right direction by offering a multi-lingual journal, thus making it accessible to a much broader base of scholars. In my own experience for instance, American environmental history is little aware of scholarship in the Netherlands or Germany where much fascinating work is being produced in their native tongues. English is already the international language of scholarship, but this new journal seems to be building necessary bridges for continental scholarship to reach a broader Anglo audience and vice versa.

orical relations with that broad region” would be too restrictive in a field that seems to be reinventing itself to be the most global of historical disciplines. Thoen and Soens stressed that the journal would accept submissions from other regions as well, though this didn’t placate the audience. The journal has already taken leap in the right direction by offering a multi-lingual journal, thus making it accessible to a much broader base of scholars. In my own experience for instance, American environmental history is little aware of scholarship in the Netherlands or Germany where much fascinating work is being produced in their native tongues. English is already the international language of scholarship, but this new journal seems to be building necessary bridges for continental scholarship to reach a broader Anglo audience and vice versa.