This will be the final post of my research blog for this summer. I’ll be flying out of Holland tomorrow and I’m reminded how leaving is always bittersweet. From a personal perspective, a month and half is an awkward length of time to live abroad. Not long enough to really feel settled, but certainly long enough to feel a significant amount of distance develop between your everyday experiences and those happening back home. This summer in particular, I was very fortunate that my research trip coincided with moments of great transition in the lives of friends and colleagues in the Netherlands. I’ve seen them get engaged, start families, and start new jobs. I’m very grateful to have been able to share in those experiences. From a professional perspective, no place beats the Netherlands for my research and this has been one of the most productive periods of my (albeit very new) professional life. With the archives, libraries, colleagues, and landscape of the Netherlands a stone’s throw away, reading, writing, and thinking about Dutch environmental history seems a natural outgrowth of waking up every day. One day out from the journey home, therefore, it’s relatively easy to take stock of what has been achieved.

Interior of the Regionaal Archief Rivierenland in Tiel. A wonderful source of information about the 1740-41 river floods.

I laid out three broad research goals in the first installment of the 2016 research blog and I’m happy to report progress on each.

1. My first goal was to get to the bottom of some historiographical inconsistencies I discovered concerning the early years of the shipworm epidemic. I elaborated on these problems in some detail in my first blog on the “unusual connections” between disasters so I won’t rehash them here. In short, the beginning of the shipworm epidemic is often dated to November 1730. According to most accounts, this was the first verifiable, consistent, explosive outbreak of the species in Dutch waters (though there is some evidence of wood borers and perhaps even Teredo navalis earlier). Several historical accounts, however, report an earlier outbreak in 1728 on the island of Goeree.(1) In my earlier blog, I noted how difficult it had been finding evidence of this supposed outbreak. The notes from the “Statenvergadering” of the Estates of Holland on 19 Aug, 1728 certainly mentioned the island and its wooden piles, but there was no mention of shipworms. The notes of a subsequent report presented in the Spring of 1729 likewise turned up no evidence of shipworms. Even following a severe storm in December of 1729 when numerous piles had been broken (the exact situation that would prompt discovery of the shipworms in Zeeland and Holland in 1730/31 respectively), the notes make no mention of the mollusks.

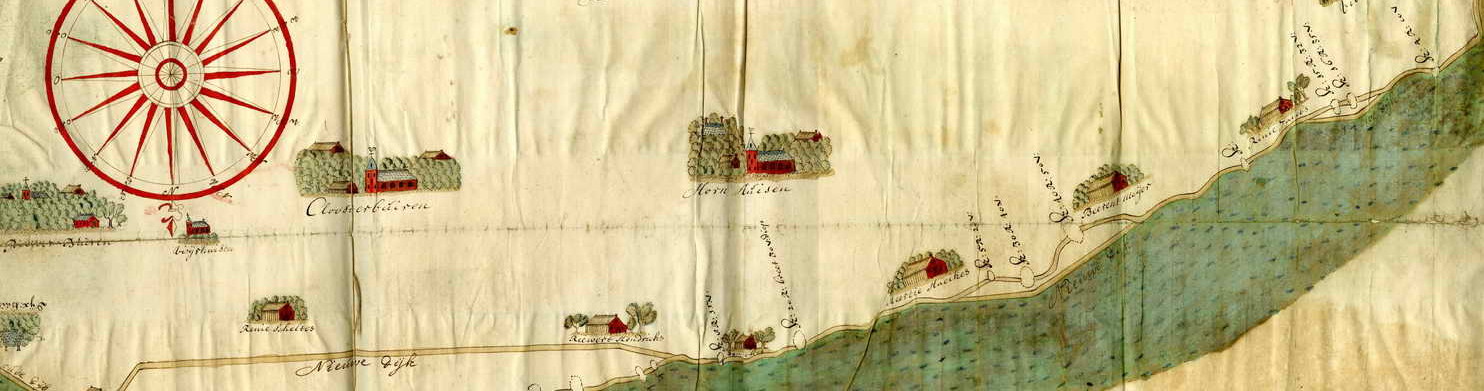

An example of a “resolutiekaart” found the resolutions of the Estates of Holland. This hand drawn map accompanied a report from surveyor Abel de Vries on the condition of the dikes along the Merwede river in the Land of Althena. The map was part of an effort to visualize disaster mitigation strategies in the aftermath of the 1726 Flood.

In fact, no mention was made of shipworms in the notes of the Statenvergadering through December 1731, even after they had been discovered in other parts of Holland!

The notes of the Statenvergadering are not the only source of information about the institutional management of water, however. The resolutions of the Estates General of Holland are a treasure trove of information. Intermixed with terse, economical notices of import restrictions, subsidies for the herring fishery, and official appointments of individuals into the bureaucracy of Holland are numerous extended reports (including correspondence, notes, and maps) of water and disaster management.(2) Perhaps this rich source of information could resolve this situation, but I would have to travel to Amsterdam to find it.

Also called the “spekkoek” for its visual similarities to the Dutch-Indonesian layer cake, the city archives of the Netherlands are housed in the Gebouw de Bazel, a Rijksmonument.

The Stadsarchief (city archive) of Amsterdam is a wonder of the archival world. Housed in the fantastic “De Bazel” building (a Chicago-style Rijksmonument on its own, built in the early 20th century), it is also one of the most well organized, digitally accessible archives I’ve ever used. Their comprehensive collection of the printed resolutions of the Estates of Holland (complete with indexing, thankfully), I expected, could offer quick insight into this problem.

Indeed, a resolution on the 10th of April 1728 noted the necessity of inspecting Goeree because “the earlier inspection is now already two years old, and in the meantime, the state of the island and the course of the current and the depths could be notably changed.”(3) The “provisional report,” however, would only arrive in 1732. An inspection at the beginning of July 1732 noted “all of the pileworks on the south side of the island are infected by the shipworms.”(4) This is the smoking gun and one that had not appeared previously in the literature. Judging from the subsequent descriptions of the mollusks in the provisional report (similar in language and detail to the “first impressions” of the shipworm elsewhere), this was likely their initial encounter. Goeree may have experienced shipworm damage at an earlier date, but this was likely the first official account in Holland. Thus, the more established historiography dating the shipworm outbreak to Zeeland seems to hold. Considering the fact that it was the Zeelandic accounts dating to 1730 that would later circulate in West Friesland rather than from Goeree (part of the same province), it makes sense that shipworms would have appeared later in the island’s records.

2. A second goal of the trip was to find new datasets for cattle plague numbers and mortality between 1769-1780. This information is necessary for a collaborative project between Filip van Roosbroeck and myself. The core question of our study is to determine why some regions of the Netherlands were more strongly impacted by the cattle plague epidemics than others.

Our original ambition was to compare regions in Flanders (Van Roosebreuck’s study area) with those of comparable regions in the Netherlands. Based on Filip’s prior work on the Austrian Netherlands, his hypothesis was that market-oriented regions (typically coastal areas) would have greater susceptibility to the outbreaks, whereas areas with less market-driven use of cattle (for instance, in the production of fertilizer and/or small-scale dairying) would be less susceptible. For this reason, I traveled to the cities Arnhem and Zwolle to find out whether their archives contained useful data series (either from mortality records or tax records on number of cattle, called hoorngeld). Our intention was to compare these eastern regions with coastal Holland and Friesland. This approach was derailed for several reasons. Firstly, because colleagues suggested that the Netherlands and the Austrian Netherlands (now Belgium) were not overtly comparable in their market-orientation or their environments. Second, I quickly discovered that the necessary data simply does not exist from the regions of the Overbetuwe (in Gelderland) or Twente (in Overijssel). As a result, we reformulated our hypothesis to address a similar question, albeit with a more tightly defined scope. What explains the regional variation within the province of Holland?

Holland is an ideal study area because of the richness of its records.

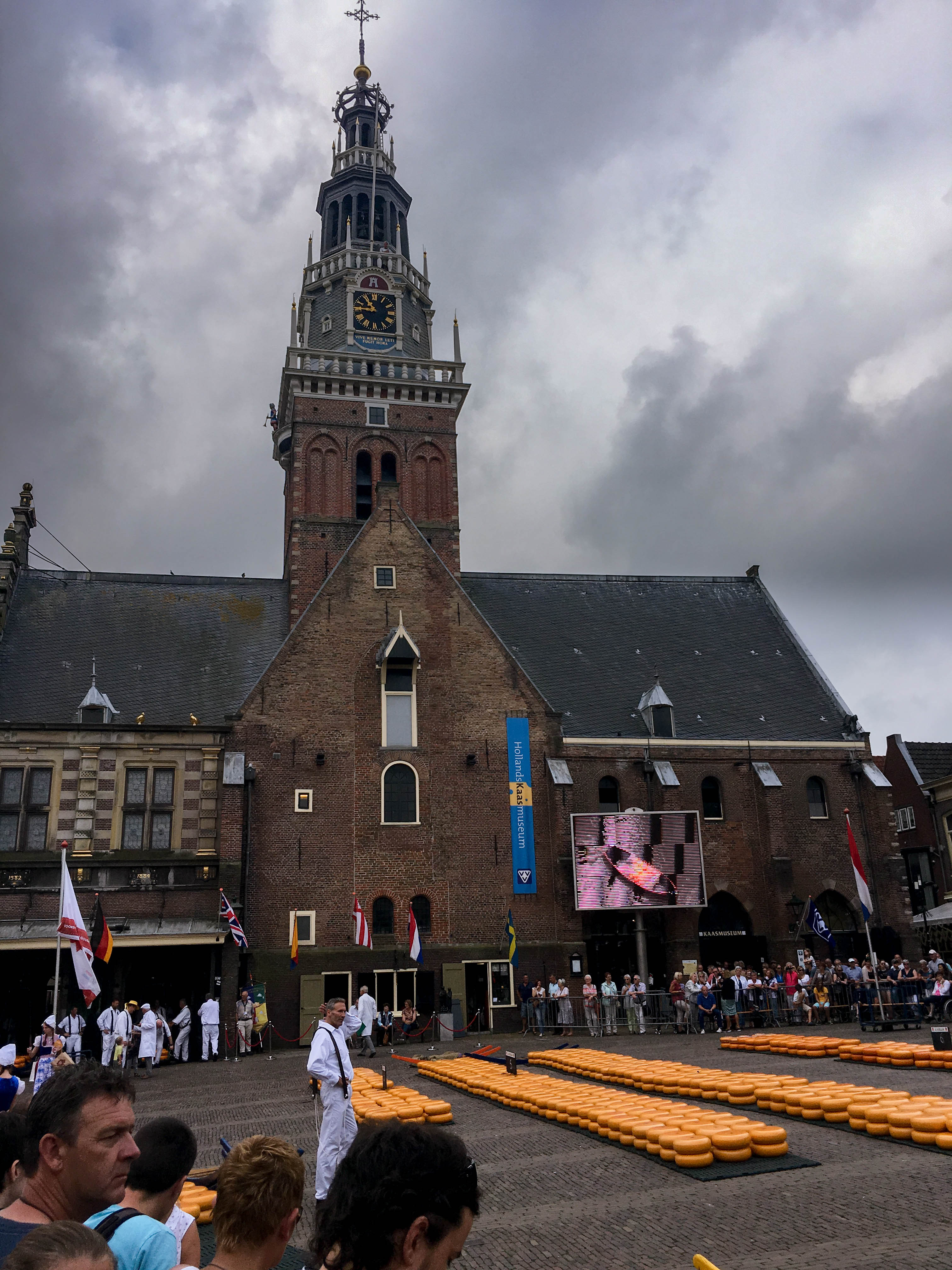

The Alkmaar Cheese Market. Alkmaar has had an operational market for centuries and the first cheese “scale” in the weigh house dates to the 14th century.

The province required municipalities to produce data series noting the number cattle infected, killed, and recovered. Despite having already collected a fairly detailed account of cattle mortality on previous research trips in Holland, we still had a small amount of archival research to do. An important subset of years at the outset of the epidemic in the early 1770s was completely absent from our records. Luckily, the Regionaal Archief Alkmaar had comparable records (though in a slightly different format). This archival visit had the added benefit of being on a Friday. Alkmaar holds their famous kaasmarkt (cheese market) Friday mornings during the summer. Although incredibly touristy, the cheese market hearkens back to the significance of this part of Holland in the early modern dairying economy. The Alkmaar kaasmarkt has a rich tradition and it’s located in the middle of an incredibly scenic, well preserved city center, but it was impossible on this particular day to observe the event without thinking about how dramatically the rinderpest epidemics of the eighteenth century would have affected this area. The research trip was successful. Having collected the data, we can now move forward with analysis. We plan to focus on the Gooi area and possibly the environmentally/culturally unique riverlands to the south, though the data and available literature will likely dictate our final decision.

3. My final (and largest) goal was to collect archival material and conduct preliminary secondary research on a river-flooding project. This was my most pressing assignment. Not only will this work be part of a collaborative research article with Toon Bosch, but I will also likely present the results of this research at the Annual Meeting of the American Historical Association in 2017 and possibly use this as the core of a final chapter for my manuscript. Aside from getting a sense of the scope of the floods and learning the history of the Dutch Rhine and Meuse (see blog), I was interested in the intersection between climate, flooding, and institutional management of the rivers in the 18th century. To what extent did river flooding in the Netherlands change in scope or severity? Did contemporaries recognize any shift and did they connect this to environmental changes? How did institutional management strategies adapt to any changes?

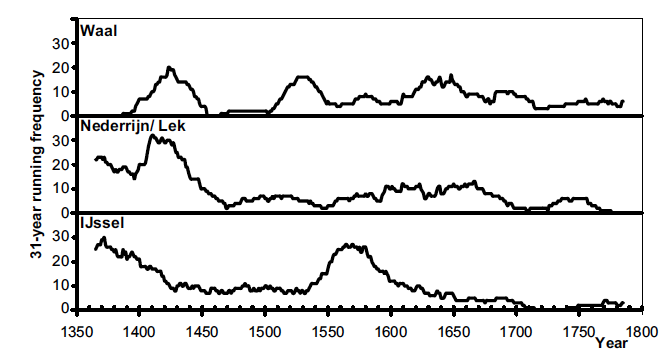

The floods of the 1740s run counter to the prevailing long term trends in river flooding. It should be noted that this graph notes frequency, not severity. Contemporaries of these floods felt that floods had been getting worse, not necessarily more frequent. Source: Glaser et al. “Historical Floods in the Dutch Rhine Delta,” Natural Hazards and Earth Systems Sciences (2003), 608.

Although still early in the process, my research has already yielded some surprising results. The floods of 1740-41 (which are my primary interest) were rather unique in origin. The floods did not occur during a period of increasing river flooding on a continental scale. Environmentally, one could even argue they were flukes. Unlike many of the river floods of the 18th and 19th centuries, these were NOT the result of ice dams. Ice dams occur when frozen sections of the rivers block discharge resulting from quickly melting snow pack (often coinciding with heavy rainfall). Ice in the lower reaches of the rivers block the discharge, forcing water over the dikes resulting in breaches. River flooding along the Dutch Rhine and Meuse are complex beasts, however, and not all floods followed this formula. This is partly because the rivers themselves are quite different. The Meuse is rain fed; whereas the Rhine’s discharge depends on both precipitation and snow melt in the Alps. The floodplains of the Rhine and Meuse interact closely in South Holland and Gelderland, but massive inundations require concurrent extreme events in the upper reaches of both river systems. The final piece of the puzzle is the human interactions with the river systems. Over the course of the early modern period, the human element would gain in relative significance. The steadily shrinking lands outside the dikes (because of drainage and peat excavation), coupled with increased sedimentation over the course of centuries necessitated increasingly higher dikes in a classical technological lock-in scenario. When a heavy rainfall event like that which occurred during the winter of 1740-41 occurred, dike breaches could occur in multiple locations.

The response was swift, but not coordinated. Cities were largely responsible for rescuing citizens in their hinterlands (a management strategy codified following the disastrous 1726 floods in the same region). Cities struggled to cope with their own inundations in the 1740s, however. Woudrichem and Heusden, for instance, were also inundated and did not have the capacity to extend help to their hinterlands. The Staten van Holland, meanwhile, offered subsidies, but no direct support. The floods of 1740-41 are well known for being the first flood recovery financed partly from citizens outside the affected regions, but help was belated and could not compensate for the extensive damages.

The final page of a special commission report on the states of dikes following the 1741 floods. The report was conducted by Willem Jacob s’Gravesande and Melchior Bolstra.

The most significant response on the part of the provinces came in the form of advisory commissions established to investigate flood vulnerability in the riverlands. The same cast of characters employed to assist in the repair of the West Frisian dikes (and previous river floods) were once again asked to lead the “scientific” investigation into the disaster. The Leiden professor Willem Jacob ‘s Gravesande and the surveyor of Rijnland Melchior Bolstra presented a report on the 24th of January 1741 detailing their suggestions. They suggested lowering the dams of the creeks to ease the pressure on the main channel, but to also encourage increasing streamflow to the sea. Their advice was the first in a protracted battle between the provinces and cities in the floodplains of the Rhine and Meuse. Despite intense interest and significant resources dedicated to the study of the river system, significant technological adaptation would be delayed until the 19th century. In the meantime, the Dutch would endure over a century of intense river flooding.

This is just one small part of the larger story of societal response and environmental change in the mid 18th century. Although the flooding seems environmentally disconnected from larger continent-scale climate changes and resulting increases in river floods, they were VERY connected to larger scale cultural and social vulnerabilities. This is not the place to outline a complete argument (especially since I have only begun developing it), but suffice to say that Dutch vulnerabilities increased during the mid-18th century largely due to political, economic, and social conditions rather than climatic factors. Social and political conflicts arising from the unique forms of “wet system building” established in the Netherlands created conditions conducive to short term adaptation, but not coordinated river management. (5) Communities tasked with maintaining dikes and provinces tasked with clearing stream-beds seemed perpetually at odds with one another and both suffered from lack of resources. Climate and society always participate to some degree in the causal dance of river flooding. The challenge for the future of this project will be to tease out their relative importance.

Although my research this summer has primarily focused on these three broad subjects, small side projects and trips occupied significant time as well. The products of several of these detours can be found in earlier blog posts. At the same time, one cannot research every day (archives aren’t open on the weekends after all…) Bike trips through the river valleys of the Meuse (in Limburg) and the Waal (in Gelderland) and the polder landscape of Leiden were fascinating introductions to landscapes I could only otherwise read about.

A vision of the boezem collecting and storing pumped polder water for eventual discharge into the Rhine. This photo was taken while biking with environmental historian Petra van Dam through the farmlands to the south of Leiden.

Donald Worster once advised my cohort of graduate students at KU to “get our boots muddy.” Environmental history, he reminded us, was first and foremost grounded in material places. It’s dirt, water, fungus, and worms. History is found in these elements just as much as it is found in centuries-old dike reports, maps, and government resolutions. I’ve done my best this summer to utilize both sets of information. I’m currently writing this final post sitting in a train heading back to The Hague. It’s a dreary, rainy day in the Netherlands and my boots are sodden. The rainwater has largely washed off whatever mud they had collected over the last month and a half. When I fly out tomorrow, I may not be bringing the literal “dirt” of environmental historical work back with me, but that’s only partly what Don meant anyway. The mud is just what you pick up along the way. It’s a reminder of the journey. What I’m bringing back is much richer.

(1) Paul van den Brink, In een opslag van het oog’ : de Hollandse rivierkartografie en waterstaatszorg in opkomst, 1725 – 1754 (Canaletto, 1998); Gerard van der Ven, Leefbaar laagland: geschiedenis van de waterbeheersing en landaanwinning in Nederland (Matrijs, 2003).

(2) Paul van den Brink has written extensively on the use of resolutiekaarten. see: “Resolutiekaarten, de Staten van Holland en de Waterstaatskartografie 1699-1795,” Kartografisch Tijdschrift 14 (1988).

(3) “de voorschreeve inspectie gedaan is nu ruym twee jaaren geleeden, dat in die tusschentyd de staat van het selve Eiland, en de loop der Stroomen, en Dieptens, merkelijk konnen weesen verandert” SvH Resoluties. 10 Apr, 1728.

(4) “alle de Paalwerken aan de zuidzyde van het Eiland door de Zeewormen zyn geinfecteert.” SvH Resoluties. Aug 1732

(5) Erik van der Vleuten and Cornelis Disco, “Water Wizards: Reshaping Wet Nature and Society,” History and Technology 20.3 (2004), 291-309.