Another summer research trip come and gone. I’m flying back tomorrow and after a final day that will be spent organizing my belongings and finding room in my pack for the books, conference swag, (and yes, gifts) I’ll be back to Omaha. It’s helpful at this point to step back and take a look at what I’ve learned. Did I complete the goals that I laid out in my first post this summer?

First and foremost were my writing goals. I now have a revised first chapter of my manuscript and have A healthy start on the second. (goals 1 and 3). This was by far the most difficult goal to accomplish, however. Finding time to write on the road was much more difficult than in years past. In comparison, last year’s trip was relatively static. I spent weeks-on-end in one location, usually The Hague. This was ideal because the material I needed was always close at hand. Sadly, this was not the case this year. I spent equal time in The Hague and Amsterdam for research, but also planned work trips abroad. My biggest regret about my planning for this summer was trying to do too much in too many places. I had an inkling this would be the case already in my first few days abroad. I tried to combine my trip to Croatia for ESEH with a good amount of writing. To my surprise and (later) dismay, this would be the most productive writing phase of the trip. Later brief visits to Antwerp and London, while useful in terms of meeting colleagues and visiting archives, were far shorter and not conducive to producing written work. Had I the chance to rework my schedule, I would have clustered all of these trips near the beginning or end of my summer travels, leaving larger chunks of time in the middle.

Completing the first chapter required careful thought and significant reading of new material related to the subject of Dutch decline. I’m consistently surprised how little is written about the subject, especially outside the realm of economic history. An exception, however, is the work of cultural historian Wijnand Mijnhardt. Mijnhardt is one of the few working cultural historians that has focused on the subject of decline, particularly in how it relates to the Dutch Enlightenment. The Enlightenment will not be a primary focus of my book project, but the attention I pay to technological and medical change necessitates greater attention than I paid in the dissertation. Peter Gay’s assertion that the Enlightenment can be characterized as a

Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation, 1966.

“recovery of nerve,” I think, works in the Dutch context, especially in the early eighteenth century. During the Enlightenment, Gay asserts, fear of change gave way to “fear of stagnation” and that “the word innovation…became a word of praise”. This fits the Dutch experience of decline quite neatly. “Recovery,” however, may not be the most apt choice of terms in the Dutch context. The Dutch seventeenth century, as has often been demonstrated, was relatively anomalous compared to its European neighbors. While much of Europe struggled to weather the tribulations that took place during the “crisis of the seventeenth century,” Dutch culture and power flourished. Part of this success must be laid at the feet of Dutch innovation in shipping, maritime technology, hydro-technology, and economic organization. “Tradition,” however, was also respected and we see even in the early eighteenth century a balance being sought between the power of innovation as rhetoric justifying change and the power of custom and tradition when seeking to maintain those gains. I have already expanded on this subject in a 2015 article on the Christmas Flood of 1717, but intend to elaborate on this much more in later chapters as well. Is it accurate to call this balance-seeking a “recovery” of nerve, or was it a “negotiation”? I’m inclined to promote the latter interpretation.

Not all of my time was spent writing, however. I visited archives in London (related to a completely separate project), The Hague, and Groningen. In the process, I found the documents needed to plug a few of the more glaring holes in my documentation. I met with colleagues in academic and social contexts, whether at their weddings, at ESEH in Zagreb, or canoeing through the web of canals and lakes extending northeast of Leiden. Each experience deepened the relationships and friendships I’ve developed with these scholars. Every year, it seems, brings new opportunities to discover new parts of the Low Countries and it’s a joy to share those experiences with friends.

The Netherlands by Canoe. I had the opportunity to explore the interlinking canals, lakes, and polder landscapes near Leiden with Petra van Dam

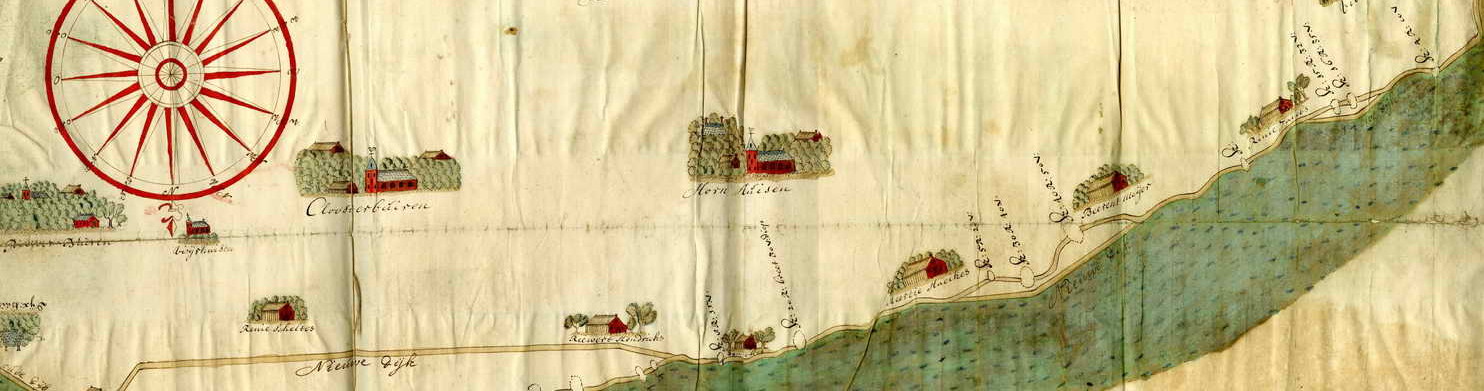

2017 was also the 300 year anniversary of the Christmas Flood. To commemorate the event, the province of Groningen, the Groninger Archieven, and several local and regional associations put together a series of events about the flood. The most prominent (and longest in duration) was a collaborative art project that featured Dutch and foreign artists developing and installing public art along roadsides and bike paths in the affected rural landscapes of Groninge

n. I took one of my final days to travel up to Groningen to see this installation. This was my first visit to this part of Groningen. I biked through towns and villages I’d only heard of from 18th century documents, and only in the context of disaster. This was a living landscape landscape, however, dotted with church steeples and omnipresent farms, far from the desolate disaster-scape I often depict in my work. My immediate reaction was confusion. Almost immediately after I stepped off the train in Winsum to rent my bike, I found it difficult to envision this region as a site of catastrophe. Biking toward the coast, however, my impression changed. North of the town of Pieterburen (now a tourist attraction because of its seal rehabilitation center), the landscape empties. The open fields filled with crops and flowers were both beautiful as well as a potent reminder of how flat and vulnerable this region was (and potentially still is) to flooding. The village of Pieterburen was heavily impacted by flood of 1717. They lost 172 people, dozens of houses, and hundreds of livestock. Little evidence of this vulnerability remains. There are no permanent markers to the flood and even the old sea dike (oude zeedijk), though still relatively large and solid, shrinks to insignificance when compared to the new, massive sea wall protecting the coast. Looking out beyond this permanent barrier, meadows scattered with cattle and sheep extend to the distance. The impression of this landscape is one of near total control. This landscape of recreation and Arcadian productivity is a monument, not to disaster and vulnerability, but the mastery of nature.

The landscape between Pieterburen and the old sea dike. The trees in a row in the distance are the old sea dike. Beyond that is a polder constructed in 1718 after the flood. Beyond that, the Wadden Sea tidal flats. The landscape is nearly completely flat with the exception of the new and remnant sea dikes and scattered housing mounds.

Roger Rigorth’s “Water Horizont” recalls the working history of the Wadden Sea as well as disaster. The nesting structures are made in a traditional weaving technique using the 17th century. Their height represents the highest level of water in 1717. For a description of the production of this work (and others along the Groninger coastline) see the Verhalen van Groningen. Video embedded below.

Of course, this is a dangerous interpretation and one which the many organizations that build and maintain these landscapes both foster and fight against. The memorialization of the Christmas Flood is an effort to temper this feeling of triumphal security. The art installations along the coast recall the Christmas Flood, but they also connect it to present-day insecurities. Some explicitly connected this historic landscape of disaster to modern climate change or instances of disasters like Katrina or Southeast Asia tsunamis. The message was clear. The most vulnerable populations are those without memory or history. Biking along the coast and back toward Groningen, it occurred to me that this is not a new challenge. In 1719, an anonymous pamphleteer described the flood and its consequences for his readers. His story was necessary, he argued, so that “eternal memory [of the flood] may be preserved.” Public art may be a novel approach, but in spirit, it captures the same mentality in evidence for centuries. Mind the next flood.

Tot volgende keer Nederland.

- Sheep graze the Old Sea Dike

- An unmarked statue along the sea dike looking toward the Wadden Sea

- Rob Sweere – Exploded View

- The Noordpolderzijl habor is the smallest in the Netherlands – one used by fisherman, now only accessible at high tide

- Stone mosaic from 1987 – shows the approaching waves, the dike, and the protected polderlands

- Unmarked statue – the slaperdijk?

- Teruhisa Suzuki – Rolling Gate