In the second installment of a three part series on the improbably connections between shipworms and river flooding in the eighteenth century, I want to focus on the subject of “expertise” in water management.

2. The same experts consulted on shipworm management also worked on river flooding

Despite the fact that coastal floods and river floods are fundamentally different and despite (or because…) shipworms were an unknown factor in both, the Estates of Holland drew on the same experts for both sets of problems. “Expertise” in water management was relatively fluid in the Dutch eighteenth century. The organizations that typically managed water defenses were waterboards. These administrative bodies were separate from provincial governments, but by the early eighteenth century both provinces and the water boards drew on the upper echelons of society for their leadership. They also both employed experienced landmeters (surveyors) and cartographers to chart their territories and offer “expert” advice.

Nicolaas Cruquius (introduced in post 1/3) was one such surveyor, as was Cornelis Velsen, the former surveyor of the oldest waterschap in the Netherlands, the Hoogheemraadschap Rijnland in southern Holland. Velsen was arguably the most influential figure in Holland’s mid-eighteenth century management. Son of the landmeter of Rijnland and himself a deputy, Velsen was well situated to assume the same role. Like Cruquius, Velsen received practical training working for the water boards before enrolling in the “Duytse Mathematique” (meaning, it was in the colloquial Dutch, rather than Latin) at Leiden University. Also like Cruquius (one could argue because of Cruquius) Velsen firmly advocated an empirical approach to river management. Rivers could only be tamed and controlled, they maintained, if they were carefully studied, measured, and mapped. In 1731, Velsen abandoned his position in Rijnland and assuming the position of clerk to the secretary of Holland. This was precisely the moment that the province faced new, unexpected challenges.

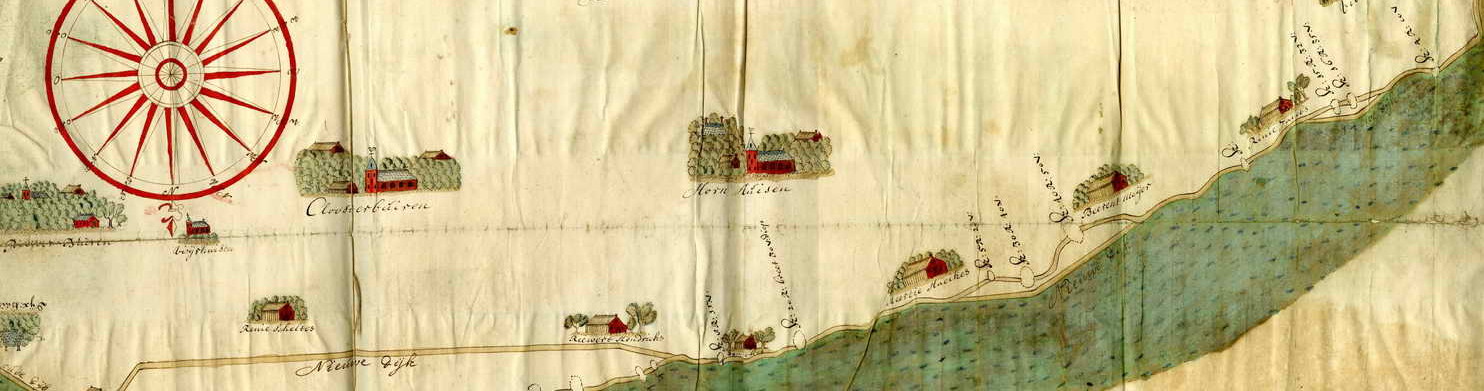

Provincial governments did not traditionally manage water-related issues in the Netherlands, but instead left those tasks to regional and local water boards. Disasters like river floods and the shipworm epidemic, however, were large in scope and devastatingly expense. They were far too expensive for single water boards to manage effectively.(1) When Velsen began his tenure in Holland, he had far more resources at his disposal than any single water board. Even the richest province in the Netherlands (Rijnland) had difficulty managing the disasters laid out before it. Between 1700 and 1750, the Dutch river lands experienced seemingly unremitting high water, dike breaches, and even flooding. (2) On top of that, beginning in 1731, dike inspections found shipworms in the piles protecting much of Holland’s coast, from Goeree in the south to the north tip of Holland on the barrier island Texel. Both Cruquius and Velsen were called upon for expert advice in both situations. In the river lands following the disastrous floods of 1726 along the Meuse and Waal, the Estates of Holland commissioned Cruquius to again produce a map. The final product was a “cartographic masterpiece.” (3) The map employed several innovations (including the use of bathymetric isolines). Velsen would become an even greater player in the management of the Rhine and Meuse branches after successive major river floods in 1740 and 1741. His publication of Rivierkundige Verhandelining in 1749 occurred at precisely the right moment with high waters threatened to break through the Lekdijk.

Cruiquius’ “cartographic masterpiece” De Rivier de Merwede, van ontrent de Steenen-hoek, Oostwaards-op tot verby het dorp van Sleeuwyk : met den Ouden-Wiel, en de Killen, die uit deselve na den Bies-Bos afloopen etc., 1729-30 Source: Utrecht University Library

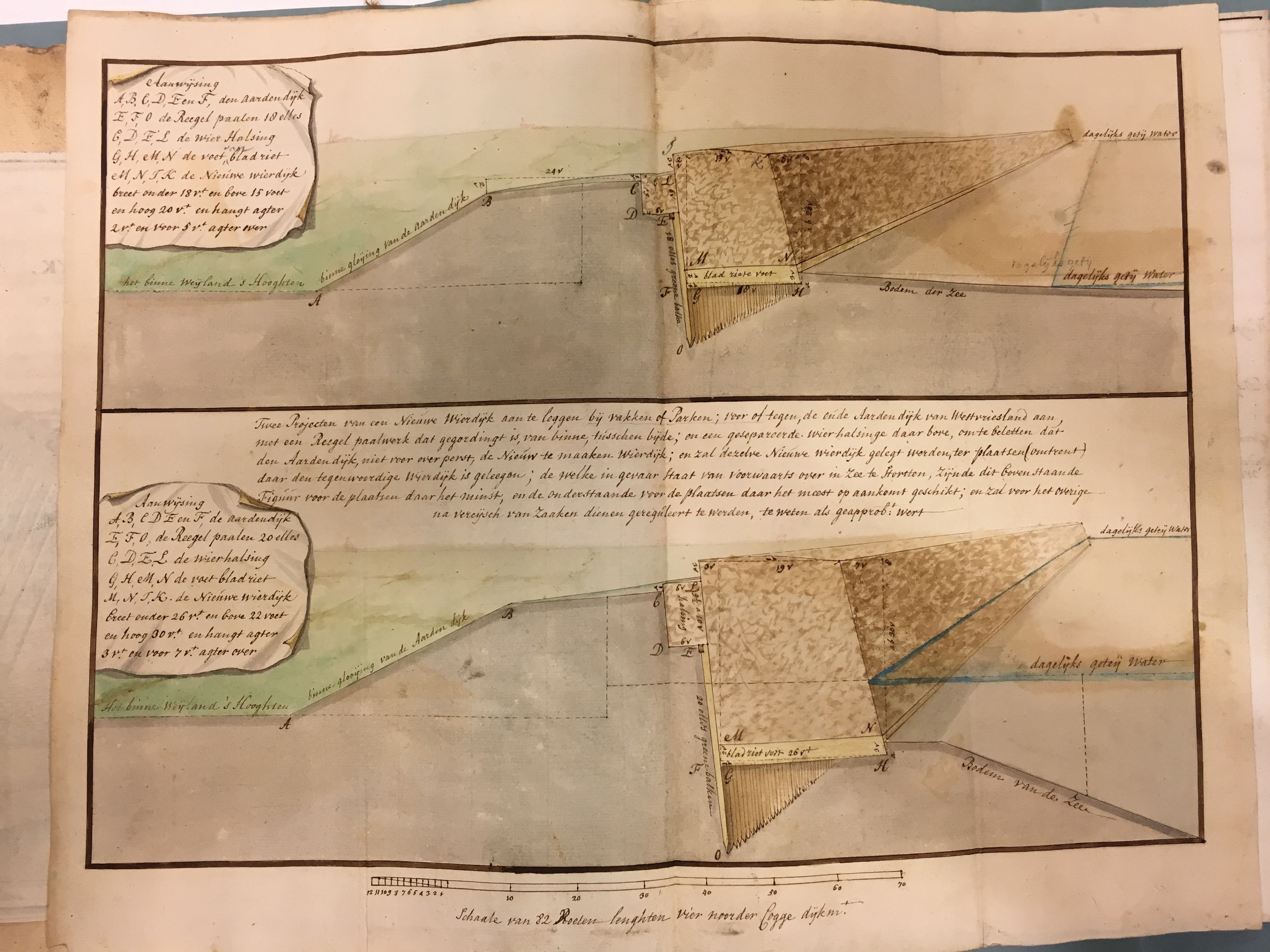

In the context of the shipworm epidemic, both Cruquius and Velsen offered expert advice to the province as well. Cruquius’ advice supported that of Jacob van der Dussen, the dike reeve of Amstelland, to completely remake the pile dike that protected the coast near Muiden.(4) This design, which removed the wooden element from the water, replacing them with a gently sloping earthen embankment, was the progenitor of modern coastal dikes. Velsen’s advice saw far less success, but his role was nevertheless important. Velsen represented the interests of the Estates of Holland, however, the province found themselves at odds with the combined power of the West Frisian waterboards. Velsen and the special provincial commission he headed advocated a solution that removed the wooden framework that typically held a seaweed “cushion” (wineriem) in front of the earthen dike. Instead, wooden piles were driven perpendicularly through the seaweed cushion to fasten it to the base of the dike. The commission funded this plan and quickly exacted it. By 1733, however, observers quickly realized how vulnerable this plan was to the relentless beating of Zuiderzee waves.

Ultimately, the West Frisian waterboards opted for a solution similar to Van der Dussen’s, replacing wierdijken with more gently sloping dikes, covered with imported stone. Although Velsen’s advice was ultimately rejected, his (and Cruquius’) participation in the dialogue represented an increasing dependency on “expert” advice on the part of provincial water management and a further connections between river and coastal protection.

(1) Due to the increasing cost and complexity of water-related problems, by the eighteenth century, provinces had assumed ever-increasing roles in the management and funding of large scale projects – particularly those that crossed provincial borders. Rivers were the prototypical interprovincial issue. The Rhine and Meuse rivers affected every province south of the Zuiderzee. It is somewhat surprising, therefore, that interprovincial management of rivers was still only nascent in the early 18th century.

(2) These included dike breaches in 1709, 1711, 1726, 1740, and 1741, not to mention nearly annual high water or even flooding without dike breaches.

(3) Utrecht University Digital Exhibit. “Cruquius’ map of the Merwede: a cartographic masterpiece” http://bc.library.uu.nl/nl/node/828

(4) C. Baars, “Herstel van de paalwormschade aan de Zuiderzeedijken beoosten Muiden,” Waterschapsbelgangen 74 (1989), 437-8.